| Alternate Names: | Wulþuz, Ollerus, Ullr, Oller, Wuldorfæder(?) |

| Iconography: | Bow, Ring, Shield, Male figure with Bow and skis |

| Domains: | Wealth, Oaths, Skiing, Hunting, Archery, Winter, Magic, Rulership, Forest |

Historical Attestations

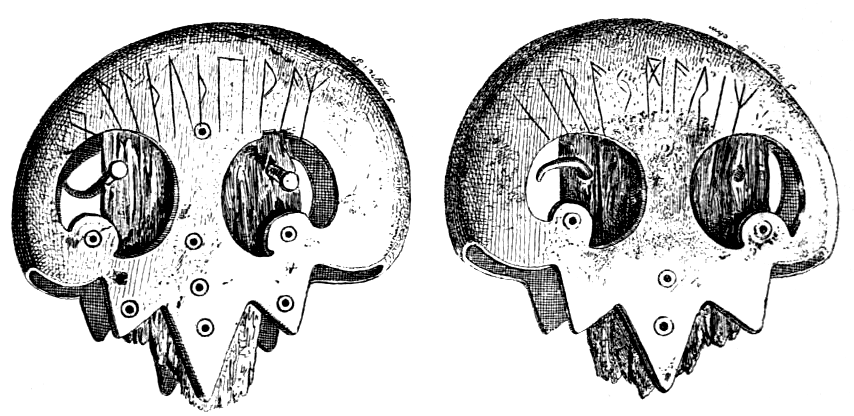

Wulð, known in various Scandinavian sources as Ollerus, or Ullr, is directly attested among the Angles solely by a piece of material culture known as the Thorsberg Chape, a bronze fitting from a scabbard found in a peat bog in Old Angeln, called the Thorsberg Moor. The inscription on this fitting reads:

ᛟᚹᛚᚦᚢᚦᛖᚹᚨᛉ / ᚾᛁᚹᚨᛃᛖᛗᚨᚱᛁᛉ

owlþuþewaz / niwaje͡mariz

“Wolthuthewaz is well-renowned,” or “the servant of Ullr, the renowned.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thorsberg_chape

However, in Old English poetry we see frequent references to glorious splendor, Heaven, or the Christian god, using the word Wuldor, the Old English near-cognate of Proto-Germanic *wulþuz appearing here on the artifact as wolþu-, meaning ‘glory’. One example is the poem Cædmon’s Hymn, ostensibly a hymn in praise of the Christian god which simply ‘came’ to the ineloquent author one night during a party, and which contains a great deal of Heathen imagery (Pollington 2011, pg 2-23) which is reproduced in its entirety below:

| Nū scylun hergan hefaenrīcaes Uard, metudæs maecti end his mōdgidanc, uerc Uuldurfadur, suē hē uundra gihwaes, ēci dryctin ōr āstelidæ hē ǣrist scōp aelda barnum heben til hrōfe, hāleg scepen. Thā middungeard moncynnæs Uard, eci Dryctin, æfter tīadæ fīrum foldu, Frēa allmectig.[5] | Now [we] shall honour / heaven-kingdom’s Ward, the measurer’s might / and his mind-plans[a], the work of the Glory-father[b] / as he of each wonder, eternal lord, / the origin established;[c] he first created[d] / for the children of men[e] heaven for a roof, / holy shaper.[f] Then Middle-earth / mankind’s Ward, eternal Lord, / after titled, the lands for men,[g] / Lord almighty. |

— Cædmon’s Hymn

As noted by Pollington in 2011, the term (weard ‘keeper or guardian’) is fraught with metaphysical implications in Germanic languages, and is a strange way to characterize the figure of Yaweh, as we tend to think of that Hebrew deity today. This poem would seem to be a great example of the crossover between Heathen and Christian ideas in Early Medieval Christianity. Also the term Uuldurfadur/wuldorfæder is a curious one as Pollington goes on to note:

The third term, wuldorfæder, is interesting in that it combines two images: a holy father-god who oversees creation, and the word wuldor ‘glory, splendour’ which is the OE form of the Norse god-name Ullr.— Stephen Pollington, The Elder Gods (2011)

What’s in a Name

It would seem reasonable to suppose that this is a form of syncretism, of Yaweh with the renowned Wolþuz, whose servant had his name inscribed on his scabbard some time in the Migration Age, perhaps around 200 CE. However, one troublesome point that must be addressed, is the fact that wuldor in Old English is a neuter noun, unsuitable by itself for the name of a god. When speaking of a spiritual ‘aura’ or an idea of ’glory’, this term is appropriate, and is used in numerous compound words, but never as a proper noun. We must therefore make the possibly controversial decision: refer to this god by one of the epithets that was applied to the Christian god as well as possibly Wulþuz himself, to refer to him by his Proto-Germanic name which may become awkward and inconsistent, or to normalize the spelling and pronunciation into a form that falls within the rules for Old English. That was the language the Angles would have been transitioning to, from so-called Proto-West Germanic. We have opted here for the third option, and after consultation with a number of linguists, have settled upon the form which alters the Proto-West Germanic spelling the least, to bring it into a form that would hopefully have been familiar to Angles in Early Medieval Northumbria, by dropping the Proto-Germanic ‘-z’ ending, deleting the exceedingly rare trailing ’u’, giving us the masculine -a stem noun form of Wulð.

For more corroborating evidence on the cult of Wulþuz however, we are mostly forced to look to attestations of North Germanic Ullr.

A God of Winter, Skiing and Skill

Saxo Grammaticus says in a highly euhemerized account of Ollerus (Ullr):

| Fama est, illum adeo praestigiarum usu calluisse, ut ad traicienda maria osse, quod diris carminibus obsignavisset, navigii loco uteretur nec eo segnius quam remigio praeiecta aquarum obstacula superaret.[8] | The story goes that he was such a cunning wizard that he used a certain bone (probably a sledge or similar conveyance), which he had marked with awful spells, wherewith to cross the seas, instead of a vessel; and that by this bone he passed over the waters that barred his way as quickly as by rowing. |

— Gesta Danorum, Elton’s translation

We also see him described in the Poetic Edda, an appearance analyzed by Guerber in 2016, where he asserts that:

As winter-god, Uller, or Oller, as he was also called was considered second only to Odin, whose place he usurped during his absence in the winter months of the year. During this period he exercised full sway over Asgard and Midgard. Uller was supposed to endure a yearly banishment thither, during the summer months, when he was forced to resign his sway over earth to Odin, the summer god.–Guerber, H. A. Myths of the Norsemen – from the Eddas and Sagas (2016)

The characterization here of Odin as a “summer god” is of course, somewhat suspect, perhaps what is meant here is that he takes over governance of Heaven and Earth, while Odin is engaged in the Wild Hunt. However, it does seem clear in the surviving poetic attestations that Ullr is a being whose might was once thought to rival even that of Odin, and who was and remains associated even today in the United States and Scandinavia with Winter, and with wintery pursuits such as skiing, hunting, fowling, and archery. The name Ullr appears in several kennings, where it indicates prowess with sword, bow, and shield. Toponyms based on his name in Scandinavia are relatively common, suggesting he was once a more central god in the Norse and Germanic pantheons than he seems to have been in the Viking Age. It also seems he, like Woden is connected with magic and the power of sorcery, as well as martial prowess. The oldest putative form of his name, PIE *wul-tus once held connotations of physical appearance or beauty, and indeed in later Norse mythology he is said to be incredibly beautiful in face and form. Also of note is the Gothic form, wulþus (‘glory, wealth’) which invites connections with more domestic functions, such as the cultivation of wealth. There is a mention of Ullr in one of the older extant Norse poems, Grímnismál , where it is written:

| Ullar hyllihefr ok allra goðahverr er tekr fyrstr á funa, því at opnir heimarverða of ása sonum, þá er hefja af hvera. | Ullr’s and all the gods’ favour shall have, whoever first shall look to the fire; for open will the dwelling be, to the Æsir’s sons, when the kettles are lifted off. |

This may be a suggestion that Ullr favored those who are industrious and maintained an orderly household, the ‘lifting off of kettles’ would seem to be a reference to preparing meals or brewing ale, and the hearth of the Migration Age (or for that matter Viking Age) dwelling was the beating heart of the home. The ability to prepare meals and brew alcoholic beverages for feasts and rituals was key to upward social mobility, and very important in forging relationships. Here we may tentatively speculate that Ullr (in the case of Grímnismál) has a hand in the accumulation of prestige or wealth, particularly when gained through ones own skill.

A God of Oaths

Ullr is also historically associated with oaths and oath giving, as is seen in Atlakviða, another of the older Eddaic poems:

| Svá gangi þér, Atli ,sem þú við Gunnar áttireiða oft of svarðaok ár of nefnda,at sól inni suðrhölluok at Sigtýs bergi,hölkvi hvílbeðjarok at hringi Ullar. | So be it with thee, Atli! As toward Gunnar thou hast held the oft-sworn oaths, formerly taken -by the southward verging sun, and by Sigtý’s hill, the secluded bed of rest, and by Ullr’s ring. |

It is widely speculated that it is Ullr who is meant by the circumlocution found in the old legal formula, áss hinn almátki, “the all-powerful god”. It is also widely thought that the motif of Ullr’s ring can be seen in the use of oath-rings in conjunction with this formula, for the swearing of oaths. Interestingly, the OE term used to gloss Latin corona, as in the divine emanation coming from the head of holy figures in religious iconography from many traditions, is wuldorbeag, ‘ring of glory’, which implies a sort of double entendre perhaps, the ring being both a glorious radiance, and in another sense an actual ring, or the inspiration for a physical ring at least, upon which oaths would be solemnized.

We now have reconstructed the lore of a god known among early Angles, whose characteristics we can only assume to be reflected in Norse Ullr. We have little reason to question that these characteristics do indeed largely come down to us from the Iron Age, given the characterization of Wulþuz as a god of ’reknown’, on an ornament intended for a sword scabbard, and corresponding North Germanic kennings that associate him with the sword, bow, and shield. We thus have little cause not to proceed on the assumption that the Ullr described in Norse sources closely resembles the Wulþuz/Wulð known to the Angles.

Ingwine Guidance

Wulð Is a god of Winter, forests, and those skills that are useful where the two domains intersect, such as woods-craft, hunting, skiing and shooting. In Norse tradition his home is called ’Yew-Dales’, the Yew being a tree prized for the suitability of its wood for making bows. He is also a god closely associated with oaths and oath-taking, and taking all of this into account, he should be considered a Yule being, and honored during the Yule-tide. As a god who prizes martial skill and renown, it seems only natural his help would be sought in the old days for success in duels, and so he may be seen as a having influence over honorable single combat in any form. He is skilled in sorcery, and would seem to have the power to overcome obstacles such as difficult terrain, as seen in his ability to cross water on his shield or on a bone, and to cross snow on skis. Due to this association, it may be wise to invoke his help when skiing, snowshoeing, sledding, waterskiing, climbing, or otherwise traversing difficult or dangerous ground. He is a god of wealth and reputation, and might assist a person with matters of honor, social mobility, the winning of accolades or leadership.