| Alternate Names: | Orvendil, Éarendel, Aurvindil |

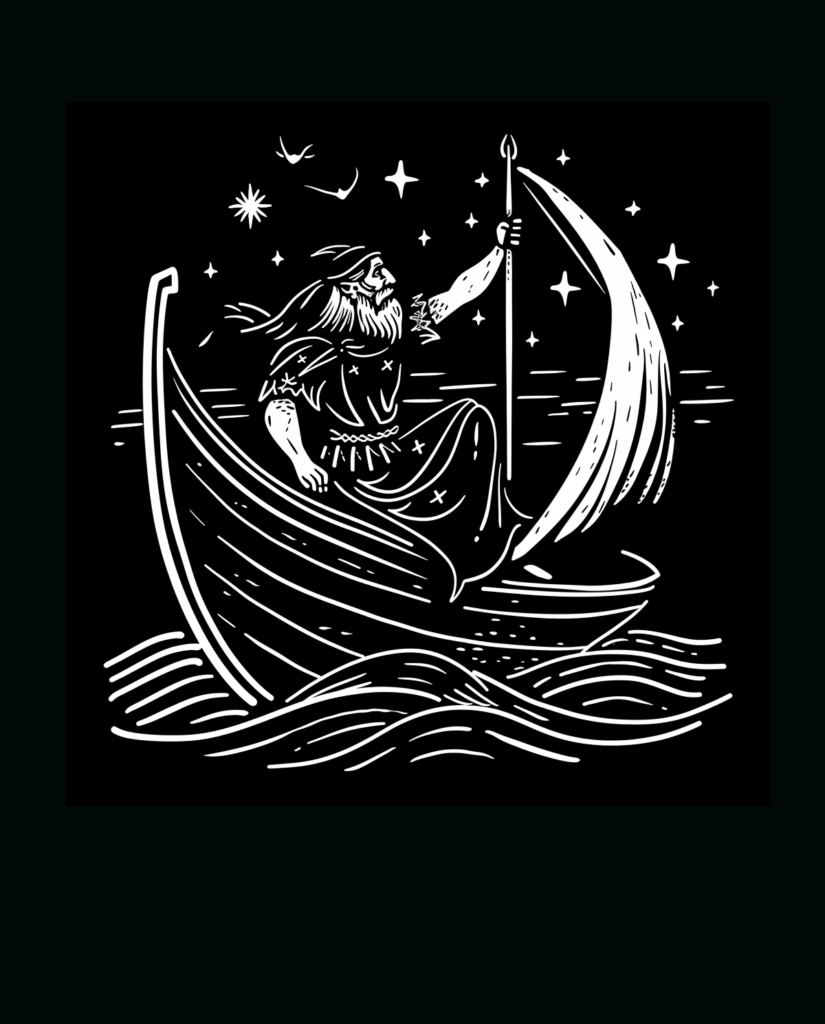

| Iconography: | The Morning Star |

| Domains: | Guidance, Light, Sea, Travel |

Table of Contents

Historical Attestations

Earendel, also spelled Ēarendel or Earendil, is a prominent figure in Anglo-Saxon pagan mythology as a god of the morning star. He is often associated with the morning star Venus, which was considered a powerful and sacred symbol in ancient Anglo-Saxon culture.

Earendel’s name is possibly derived from the Old English words “ēare,” meaning “sea,” and “endel,” meaning “shining one.” Other etymologies have been proposed, but seem less likely. This suggests that he was associated with the sea and the sky, and was possibly considered to be a powerful and radiant figure. The Old English term “ēarendel” (and its variations like “eorendel” and “earendil”) is found only a handful of times within the entire corpus of Old English literature. Its usage often serves to translate Latin terms such as “oriens” (rising sun), “lucifer” (light-bringer), “aurora” (dawn), or “iubar” (radiance). Scholar J. E. Cross points out that the word likely initially signified the advent of light or the very inception of illumination, essentially embodying the concept of a harbinger of brightness1Cross, J. E. (1964). “The ‘Coeternal beam’ in the O.E. advent poem (Christ I)ll.104–129”. Neophilologus. 48 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1007/BF01515526. ISSN 1572-8668. S2CID 162245531. This meaning subsequently evolved to encompass broader notions of radiance or light itself. Tiffany Beechy, a philologist, elaborates on this by suggesting that the Anglo-Saxons might have envisioned “ēarendel” as a semi-mythical entity that epitomized both a natural event, like the sunrise, and a celestial body, specifically the morning star2Beechy, Tiffanya (2010b). The Poetics of Old English. Ashgate. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-7546-6917-3. This duality casts “ēarendel” not just as a linguistic term but as a cultural symbol intertwining astronomical phenomena with mythic personification. The oldest attestation of this name may occur in the Gothica Bononiensia, a sermon from Ostrogothic Italy written in the Gothic language not later than the first half of the 6th century, and discovered in 20093 Gothica Bononiensia: Analisi linguistica e filologica di un nuovo documento, Aevum, 87 (2013), fasc. 1, pp. 113-155), ISSN 0001-9593.

In Anglo-Saxon literature, Earendel is often depicted as a powerful and benevolent figure, who brings light and hope to the world. He is associated with the dawn, and is said to herald the arrival of the new day. He is also associated with the concept of hope and guidance, and is often invoked in times of need or trouble.

Earendel’s association with the morning star Venus, which appears in the morning sky before the sun rises, further reinforces his role as a bringer of light and hope. The morning star was also considered a symbol of new beginnings and the triumph of light over darkness.

In Norse mythology, as detailed in Snorri Sturluson’s “Prose Edda,” there’s a short but captivating story involving Thor, (Thunor) and a mythological figure, Aurvandil, which is cognate with OE Earendel. During a perilous journey from the giant’s land of Jötunheimr, Aurvandil’s toe freezes. In a gesture that blends compassion with cosmic creativity, Thor breaks off the frozen toe and throws it into the sky, where it becomes a star known as Aurvandilstá, or “Aurvandil’s Toe.”4Bellows, H. A. (1969). The poetic edda. Biblo and Tannen.

Another possibly related account was penned by Saxo Grammaticus, who is known for his euhemerizations of Germanic gods. Horwendill, in Saxo’s account, is a (euhemerized) Jutish chieftain who, along with his brother Feng, is noted for his valor and prowess. King Rorik of Denmark appoints Horwendill and Feng as the governors of Jutland, recognizing their service and ability to protect the land. Horwendill’s fame and fortune grow even further when he marries Gerutha (Gertrude in later versions), the daughter of King Rorik, and they have a son named Amleth (who would inspire Shakespeare’s Hamlet).

The narrative of Horwendill includes a significant episode where he gains renown for slaying Koll, the King of Norway, in single combat during a sea battle. This victory at sea not only cements Horwendill’s reputation as a warrior but also showcases his abilities as a leader in maritime warfare, hinting at the thematic connection to sailing and naval prowess.

While Horwendill’s story is distinct from the more celestial and mystical associations of Earendel, the elements of heroism, battle, and the sea provide a thematic link that ties back to the broader tapestry of Germanic and Norse legend, where figures often embody multiple aspects of the culture’s valor, exploration, and cosmology.

In Anglo-Saxon paganism, Earendel may have been worshipped as a god of the sea and the sky. He may have been invoked in rituals and offerings related to the dawn and the morning star, and may have been considered a powerful and benevolent force that brought light and hope to the world.

Earendel is also connected to the Christian tradition, as he is seen as a precursor of the Christ and a symbol of salvation. He is also reimagined as an angel of the highest rank, as he is mentioned in the “Crist” poem and in the Exeter Book, Riddle 77.

It is also possible that the name Earendel was used as a personal name among the Anglo-Saxon people, reflecting the importance and reverence of this deity.