in this lorehoard we will set out to describe the tenants, beliefs, rites, and historical underpinnings of what we call Ingwine Heathenship or in Old English, Ingƿina Hæðenscipe. Firstly, it is important to say at the outset that this author takes for granted that several recent incarnations of modern “Anglo-Saxon Heathenry” already exist, and it is not within the scope of this work to critique or comment on them extensively. It should be noted, that the tradition described in this lorehoard an be viewed as the successor to the reconstructed one my colleagues and I first espoused publicly in the early 2000s as Fyrnsidu. However, due to the fragmentation that movement suffered, we do not seek here to revive it per se, but choose to deploy that term now exclusively to describe pre-conversion practices. Instead, we hope to start over, to define a new branch of modern Germanic polytheism/animism from scratch. We will use the terms Heathenry and Heathenship interchangeably, however we will generally prefer Heathenship, as it is an actual pedigreed English word and translates the Old English more exactly. Whereas Heathenry on the other hand is something of a neologism. We begin by defining the scope of the ancient pre-Christian traditions that we will use to form the basis of Ingƿina Hæðenscipe, which is literally “The Heathen Ways of the Friends of Ing”. So, in this context, who are the “Friends of Ing?”

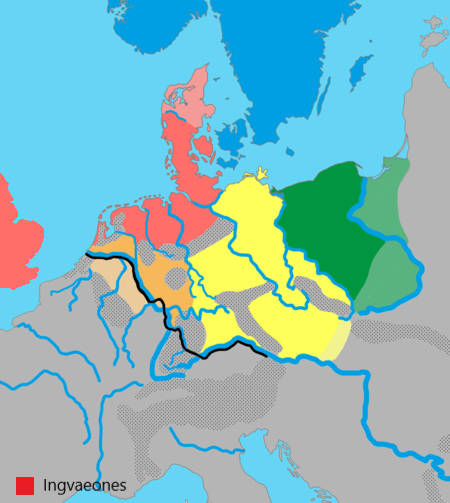

The Ingvaeones

The North Sea Germanic (also called the Ingvaeonic) language group, is a family of Germanic languages that is comprised of Old Frisian, Old Saxon, Old English, and their descendants. This language group corresponds almost exactly to one of the three groupings of Germanic tribes described by the Roman scholar Tacitus in his work Germania. He relates there that the Earth-born god Mannus had three sons, Itaev(Istio?), Irmin, and Ing, who sired three major groupings of Germanic peoples:

To Mannus they ascribe three sons, from whose names the people bordering on the ocean are called Ingaevones; those inhabiting the central parts, Herminones; the rest, Istaevones. Some however, assuming the licence of antiquity, affirm that there were more descendants of the god, from whom more appellations were derived; as those of the Marsi, Gambrivii, Suevi, and Vandali; and that these are the genuine and original names.

The Ingvaeonic peoples, those descended of Ing, are those who settled about the North Sea, and later, the British Isles. These peoples included the the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Chauci, and Frisians. If we “de-latinize” the term Ingvaeone, we have Ingƿine, the “friends of Ing”. Interesting, in Beowulf, an epic written in Old English, we see that Hrothgar is repeatedly referred to as a “lord of Ing’s Friends”. This shows us two things. First, that the English, whose own name seems to invoke descent from Ing (Pollington, 2011) had such a term in their lexicon, and also that the poet felt it appropriate to apply it to a king of the Danes. This would possibly indicate that the Heathen Danes, as protagonists in the story are being afforded the “courtesy” of not being called out as Heathens by the Christian poet, but certainly it is the case that the dynasties of West-Germanic kings and nobles and their North-Germanic cousins were intertwined in ways we will probably never be able to clearly discern now. The genealogies offered for Hrothgar and those of ancient Angeln seem to lay claim at times to the same kings, including the mythological hero Sceafa, from whom both Hrothgar and the later kings of the Angles claim descent. Suffice to say, that the accounts of Danish and English royal dynasties of pre-conversion times are muddled and contradictory at best, and when we speak of the Ingwine here, it is not the Danes but the West-Germanic, or Ingavaeonic language family we speak of.

These ancient tribes inter-communicated, traded, and would have found one another for the most part, mutually intelligible in conversation. This grouping serves as a logical boundary marker for the kinds of primary sources and historically attested traditions we prefer to include in a reconstruction that could fairly be characterized as “Anglo-Saxon” Heathenship. To source a broader cross-section of Pan-Germanic lore becomes increasingly problematic as the scope broadens, as a “religion” based so broadly across so many Germanic tribes would include material unlikely to be mutually familiar among those constituent tribes. In other words, incorporating more and more polytheistic German practices across a larger swathe of time and space in an effort to harvest more source material, actually hinders “historical authenticity” as the resultant Neo-pagan faith would be unlikely to look all that much like anything that the various tribal contributors would recognize. With that said, it would probably be agreeable to add cults or practices that were found among neighboring Herminones, such as the Cherusci, who would have interacted with Ingaevones in what is now the Netherlands. This is the sort of decision best left to practitioners to decide for themselves, but it should be noted the author would prefer to incorporate such elements sparingly, and with care given to maintain the essentially West Germanic flavor of Ingwine Heathenship.

And so for our purposes then, the Ingƿine (or Ingwine) of Antiquity were Heathen members of the Anglo-Saxon English and North Sea Germanic tribes. By extension, the modern Ingwine are the cultural and spiritual descendants of these same peoples, regardless of their genetic makeup. A Heathen person who speaks English, Dutch or even German, who wishes to follow in the spiritual footsteps of the ancient English, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians is entitled to become an Ingwine, a Friend if Ing.

A more localized tradition on the other hand, for instance “Mercian Heathenry” or “Frisian Heathenry” is equally problematic for a different reason; insufficient surviving lore to establish a working, modern practice. While the reader (ostensibly a modern Heathen practitioner) is encouraged to incorporate such practices as they deem fit into their own interpretation of Heathendom, it is part of the stated purpose of this site to create a template that cleaves as closely as possible to a legitimately historical underpinning. More will be said on this point later, but for now, let’s address the question of time.

The Original Heathen Era Was a Long Time

If one were to define Heathendom or paganism in the broadest possible sense; a spiritual, political, and/or social framework that involves theism, but does not stem from the faiths of Abraham— then Europe was “Heathen” from the dim antiquity of pre-history until arguably the 5th Century CE. Heathendom continued to exist covertly from that point until at least the 9th Century in England and Western Europe, and even longer in Scandinavia. Given this, and given the absence of evidence for a broadly accepted historical Heathen “Orthodoxy” in the sense that a Christian might understand the concept, would an early Iron Age German from the forests of Central Europe consider a Viking warrior from Norway in the 10th Century “co-religious”? This is certainly doubtful. Both are Heathens, certainly. But an English Monk from the time of the conversion, and the pastor of a Southern Baptist church in Alabama in the 21st Century are both Christians, as well. If they met, how much would they have in common?

It is our intention to source lore from the 1st Century CE, through the 5th, as our primary time period of interest, and this is already quite a great span of time. We will include curated elements of folk lore that stem as well from the 6th-9th Century, where it can be assessed as being genuinely Heathen with a reasonable level of certainty.

From the 10th Century onward, we will show increasing skepticism, and certainly it should be said that we will treat the Norse and Icelandic warrior poetry of the 12th Century and onward as being both unreliable from a standpoint of authenticity, and somewhat outside the scope of Ingwine Heathenship, based on its origins in North Germanic, rather than West Germanic tradition. While we may turn to such sources for clues or for confirmation of a particular thesis, we will rely on the Eddas and Icelandic sagas as sources of last resort. It is not the Norse, nor even Danish but English Saxon tradition we wish to place at the forefront here, at least as a template for others to follow as they seek to establish their own sida, or “traditions”.

To this end, we examine the surviving lore, and recapitulate it as objectively as possible in order to make some sound, defensible, affirmative statements about what Anglo-Saxon Heathendom was, so that we can establish some broad guidelines that define what Heathendom can be now. It is worth making clear at this point if it not already, that Ingwine Heathenship as described in this text is “Anglo-centric”, and when an ancient language is used to describe a concept or being, that language is typically Old English. The author as well as presumably the great majority of the audience is Anglophone, and therefore our cognitive bias toward the Heathen viewpoint of English and English Saxon peoples is not only acknowledged, it is an explicit part of our methodology in describing Ingwine Heathenship. We will use material from Frisian and even Danish sources in our work, but the point of reference throughout is that of an “Anglo-Saxon” Heathen.

The Original Heathen Era Was Also a Long Time Ago

The inescapable reality is, that the passage of time, combined with the antipathy of the Anglo-Saxon (Catholic) Church during the period of the conversion, has had a devastating effect on the preservation of Heathen traditions from the Early Medieval period and earlier. Timber structures have long rotted away, inscriptions have faded, oral traditions have been broken, or written down in such a way as to obscure their pagan origins. There is very little chance that a truly comprehensive picture of the theological landscape of early Anglo-Saxon England, or a fully detailed understanding of the rites of our Heathen forbears will ever come to light. While new techniques and new scholarship in the field of archaeology may continue to enrich our understanding of Heathen burial customs, and even teach us more about their use of tools, weapons, ritual paraphernalia and sacred spaces, a thorough “reconstruction” of a complete, Iron-Age pagan Germanic religion complete with liturgy is simply never going to arrive. A time-machine would be required to obtain it, at this point.

However, while an authentic and complete reconstruction of West Germanic Heathenship (or any Germanic Heathen tradition for that matter) is not currently possible, a revival, or perhaps, a revivification of English, Frisian and Saxon Heathenship in the modern era is certainly possible and has already been underway for some while, though in some cases, it remains trammeled by a curious insistence on certain very particular (and even idiosyncratic) notions of “historical authenticity”, that can never be fully realized. To be perfectly transparent, the author has, based on the foregoing, applied ancient ideas, rites, and customs, in ways that probably (almost certainly) vary from their Early Medieval or Iron-Age applications, even to the extent of being patently modern reinventions. In such cases, it will be so noted, and evidence that provides the historical basis for such reinventions will be provided, along with the rationale for our interpretation.

Well attested beliefs, rites and customs are given greater weight by-and-large than those which are not, in the interest of maintaining as strong a connection as possible to the ancient customs of our forbears. Nevertheless, it is the intention of the author to render these ancient customs (to the extent we can truly know them) into a form that modern practitioners can enjoy and use, and most importantly, build upon without recourse to extensive training in archaic skills and languages, and without recreating the social and economic structures of Medieval England.

In fact, this author would advocate that undue emphasis has been placed in recent years upon somehow resurrecting a complete Heathen religion that can be held up as being legitimately ancient, when in fact the remaining bits of lore we do possess point to an ever-evolving, inherently unorthodox, and flexible complex of traditions and cults, that was constantly growing and changing to accommodate the ecological, economic, and political realities of migrating and maturing Germanic cultures. The sort of monolithic “Pan-Germanic” pagan orthodoxy that some modern Heathens seem to crave, very likely never existed, and would not have remained unchanged from the Iron-Age until today, even if it had!

Given this, and the philosophical approach outlined below, the author seeks to bridge the gap between inappropriate projection of modern Neo-Pagan conceits onto ancient Germanic tribes, and the sort of retrogressive approach to Heathenry that often seems to devolve into a pointless intellectual exercise, or in a sort of “historical re-enactment” at best. Heathenry is not, in this author’s view, simply a performative niche lifestyle, best suited to living-history villages and museums.