| Alternate Names: | Bēow, Bēo |

| Iconography: | Barley, Barleycorn |

| Domains: | Brewing, Harvest |

Table of Contents

Historical Attestation

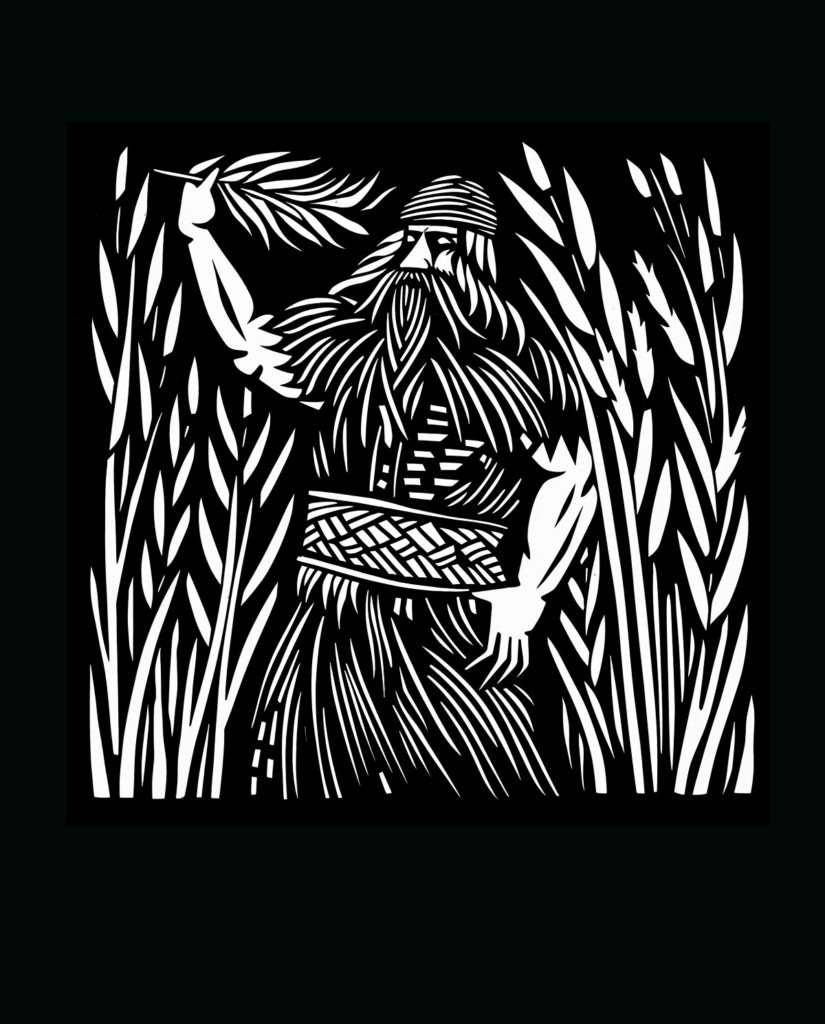

Beowa, also spelled Bēow or Bēo, is a heretofore somewhat obscure figure in Anglo-Saxon Heathen mythology as a spirit of barley and the god of agricultural fertility. He is also known as the Barley spirit, and is associated with the growth and harvest of barley, which was a vital crop in ancient Anglo-Saxon culture. He is primarily attested in two genealogical lists: the “Anglian Collection”1Dumville, David N., editor. The Anglian Collection of Royal Genealogies and Regnal Lists. Anglo-Saxon England, Vol. 5, Cambridge University Press, 1976. and the “West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List.”2Kirby, D.P., and T.J. Oleson, editors. The West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List. Early Medieval Kingship, edited by P.H. Sawyer and I.N. Wood, University of Leeds, 1977. In these sources, Béowa is listed as an ancestor of several Anglo-Saxon kings.

Divine Ancestry

Béowa is mentioned as the son of Scyld Scefing (Shield Sheafson) and the father of Sceafa. His name is associated with agricultural terms, suggesting a connection to fertility and the earth. Béowa’s role is less explicitly detailed in surviving texts, but his inclusion in these lineages implies he is a link in the chain of divine ancestry. This association reinforces the idea that the prosperity and legitimacy of the royal lineages are divinely ordained. In the “Anglian Collection,” he appears in the genealogies of the kings of Lindsey, while in the “West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List,” he appears in the genealogy of the West Saxon kings. These genealogies were often used to establish the divine or heroic origins of ruling dynasties. Béowa, Sceafa, and Scyld together form a triad that embodies the mythic foundation of certain Anglo-Saxon royal houses. Their stories highlight themes of divine intervention, miraculous origins, and the agricultural prosperity that sustains the community. By tracing their ancestry to these figures, Anglo-Saxon kings could claim a divine mandate to rule and connect themselves to a mythic past that justified their sovereignty.3Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price, Penguin Classics, 1990.

The story of Scyld Scefing is famously echoed in the opening lines4Heaney, Seamus, translator. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. of the epic poem Beowulf, where Scyld’s arrival by sea and his subsequent rise to kingship are recounted. While Béowa himself does not feature prominently in Beowulf, his genealogical role as a precursor to Scyld and Sceafa is part of the larger mythic framework that underpins the narrative.

Echoes in Norse Myth

Béowa, whose name is linked to barley or grain, embodies the agricultural abundance essential to the prosperity of his society. This focus on barley connects Béowa to the essential practices of farming and brewing, which were central to the sustenance and social rituals of the Anglo-Saxons. If we look to Scandinavian mythology for comparative purposes, we quickly see this same theme emerging. Byggvir, a minor deity in Norse mythology, explicitly represents barley and brewing. His name directly translates to “barley,” and he serves Freyr, the god of fertility, further emphasizing his role in agriculture. Byggvir appears in the Poetic Edda5Bellows, Henry Adams, translator. The Poetic Edda. Princeton University Press, 1936., specifically in the poem “Lokasenna,” where despite being mocked by Loki, he asserts his importance within the divine community. Byggvir’s presence highlights the cultural significance of barley and beer in Norse society, where brewing was both a daily activity and a ritualistic practice.

Freyr himself is often identified with Yngvi (Ingvi), a divine ancestor of the Yngling dynasty in Sweden.6Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Translated by Lee M. Hollander, University of Texas Press, 1964. Anglo-Saxon genealogies parallel this tradition, with figures like Scyld (Shield Sheafson) and Sceafa (Sceaf) tracing their lineage back to a god, though in the case of most surviving versions, it is Woden, not Ing, who is the god ancestor of Beowa. It should be noted, that the royal genealogies of the Scyldings/Skjöldungs represent an obvious blending of traditions, and that Byggvir is not placed in the same position relative to Swedish Skjöld that Beowa is to Scyld. Still. this connection suggests that Béowa, associated with barley and agriculture, descends from a harvest god (which West Germanic Woden is, among other things), echoing the Eddaic tradition where Byggvir is a retainer or kinsman of Freyr. Texts like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the epic Beowulf emphasize the divine ancestry of these figures, underlining the cultural importance of linking kingship with divine favor and agricultural prosperity. This shared heritage highlights the role of divine progenitors in ensuring the fertility and legitimacy of royal dynasties across Germanic cultures.

While Béowa and Byggvir stem from different Proto-Germanic terms (bewwō and bugjaz, respectively), both are linked to the same PIE root *bhares-. This shared ancestry highlights the deep cultural significance of barley in Indo-European agricultural societies and how similar terms evolved in the Anglo-Saxon and Norse languages to represent this essential crop.

Anglo-Saxon Cultural Resonance

Béowa is depicted as a powerful and benevolent spirit, who ensures the fertility of the land and the success of the harvest. In this role, he is closely connected to the natural cycle of the seasons and the cycles of planting and harvest. He is also associated with the abundance and prosperity of the community, as a bountiful harvest would provide food and resources for the people.

Elsewhere in Anglo-Saxon literature, Béowa may be obliquely invoked in connection to the agricultural cycle. For example, in the “Laws of Æthelberht,” which is an Anglo-Saxon legal code from the 7th century7Attenborough, F. L. (1922). The laws of the earliest English kings æthelberht I to æthelstan. The University Press., there are specific laws related to the sowing and reaping of barley, which may reflect the importance of Beowa in the agricultural practices of the time.

Béowa is also closely associated with the character of John Barleycorn in English folklore. John Barleycorn is a personification of the barley plant and its transformation from seed to beer. The character is often associated with the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, as the barley plant is sown in the spring, grows during the summer, and is harvested in the fall. The barley is then transformed into beer, which is consumed and celebrated during the winter. In this sense, John Barleycorn and Beowa share similar attributes and may have been mythologically interconnected.

Three Men from out of the West

A correlation that may be worth considering, is the idea that the three divine ancestors (Béowa, Scyld, and Sceafa) in Anglo-Saxon mythology could be connected to the three men (sometimes kings) in the folk song “John Barleycorn”. Both sets of figures embody themes of agricultural fertility, death, and rebirth, crucial to agrarian societies. The three kings in “John Barleycorn” personify the harvesting and transformation of barley into beer, reflecting the life cycle of the crop.

The worship of Beowa may have taken place during the planting and harvest season, with rituals and offerings made to ensure a bountiful crop. One example of such propitiation of the grain spirit from folklore, is the tradition of saving the last sheaf of corn during the harvest, believed to contain the spirit of the corn. This sheaf, often referred to as the “Corn Mother” or “Corn Dolly,” was treated with great reverence and sometimes hung up to ensure a good harvest the following year. In some regions, it was scattered back onto the fields in spring to return the spirit to the earth, symbolizing the cyclical nature of life and fertility.8Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Macmillan, 1922.

It is also believed that Béowa was a chthonic deity, meaning that he was associated with the underworld. This association may have been made due to the underground growth of barley and its connection to the cycle of death and rebirth.

Ingwine Guidance

In conclusion, Béowa is a prominent figure in our contemporary Anglo-Saxon Heathen mythology, as the spirit of barley and the god of agricultural fertility. He is closely connected to the natural cycle of the seasons and the cycles of planting and harvest, as well as the abundance and prosperity of the community. Worship of Beowa would be appropriate during planting or the early part of the harvest season, with rituals and offerings made to ensure a bountiful crop. The association of Beowa with the underworld further emphasizes the importance of agriculture and the cycle of life, death and rebirth in ancient Anglo-Saxon culture.