| Alternate Names: | Foste, Forseti |

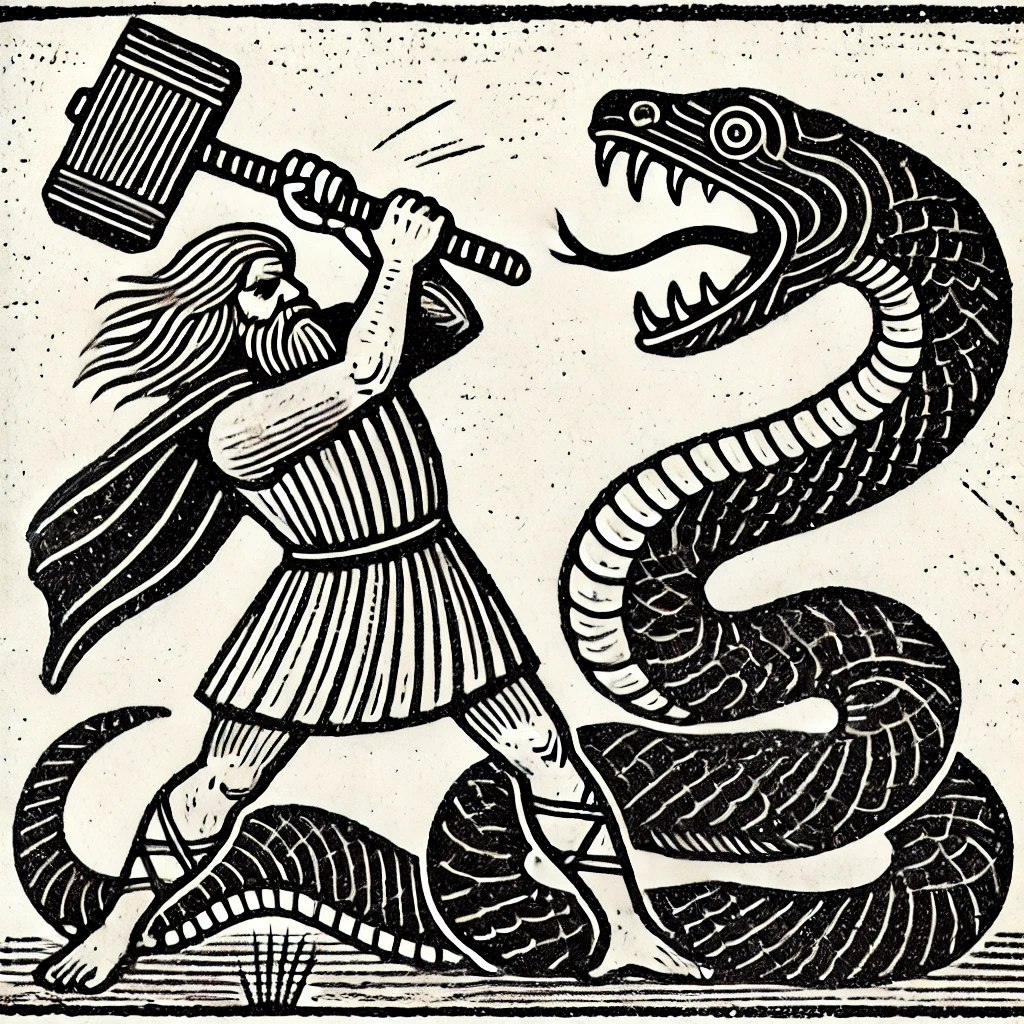

| Iconography: | Golden Axe, Boat, Well |

| Domains: | Law, Sea, Travel |

Historical Attestations

Now whilst this energetic preacher of the Word was pursuing his iourney he came to a certain island on the boundary between the Frisians and the Danes, which the people of those parts call Fositeland, after a god named Fosite, whom they worship and whose temples stood there. This place was held by the pagans in such great awe that none of the natives would venture to meddle with any of the cattle that fed there nor with anything else, nor dare they draw water from the spring that bubbled up there except in complete silence.

— The Life of St. Willibrord1Talbot, C. H. (1954). The Anglo-saxon missionaries in Germany: Being the lives of SS. Willibrord, Boniface, Sturm, Leoba, and Lebuin, together with the hodoeporicon of St. Willibald and a selection from the correspondence of St. Boniface. Sheed and Ward.

Fosite is a god highly venerated among Frisians of the Early Medieval period, and almost certainly since before that. The island Fositeland, referenced in the citation above, is generally accepted to refer to Heligoland (‘Holy Land’), a North Sea archipelago. His name is thought to mean (‘One who Presides’), in reference the fact that he was considered a god of order, reconciliation, and law, as well as quite probably, commerce and the sea. This portfolio reflects the importance of maritime navigation to the people of this region, situated between Scandinavia and modern day Holland. The philologist Hans Kuhn, in his Kleine Schriften IV: Aufsätze aus den Jahren (1968-1976) asserted that accounting for the Proto-Germanic sound shift, this name is “linguistically identical” to the Greek Poseidon, and that the deity was perhaps introduced to the Frisians by Greek amber-traders in antiquity. As of this writing, this seems to be largely uncontested in academic spheres, leaving this author to conclude that it is indeed probable that these are references to the same, essential deity. This would contrast with many other cases of Interpretatio graeca or Interpretatio romana, where the names of Germanic gods in literature have simply been glossed using the names of classical Mediterranean gods, more familiar to a Latin or Greek speaking audience, such as in the case of Tiw and the Roman Mars, whose names are not etymologically related and share only superficial traits in common.

In one of the few surviving myths concerning Fosite, we see the two portfolios mentioned above, sea-travel and law, coincide in a most interesting way. In the Codex Unia2Bremmer, R. H., Laker, S., & Vries, O. (2014). Directions for old frisian philology. Editions Rodopi, B.V., a tale is told, that King Karl Martel, having conquered Frisia, demanded that their lawspeakers write down their laws in a codified form, for his official review. Due to legal disagreements, the twelve lawspeakers cannot comply. After being asked several times, and being unable to produce a written law code each time, King Karl poses them the odious choice: be executed, become slaves, or be placed in a strong ship with no oars or rudder, and cast adrift on the sea.

Thinking that the last choice represented the least terrible choice, they elect to be set adrift. The twelve men drift aimlessly for some time, arguing over what if anything they can do now to better their situation, when a thirteenth man appears in the vessel, as if from nowhere, with a golden axe over his shoulder. He proceeds to direct the assembly in the creation of a code of laws, and when done, he uses the axe itself to steer the ship to land saving the lawspeakers, and then he hurls the axe into the land. Where the axe falls, a spring bubbles forth, and from that moment forward, the tradition has it, the spring and the island have been sacred to Fosite, with whom folklorists have identified the thirteenth man. The mysterious figure disappears at the end of the story, but the Frisians have their laws.

Some aspects of this story appear reflected in the description of the Norse god Forseti in Gylfaginning, a story in the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson3Sturluson, S., Young, J. I., & Nordal, S. (2012). The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse mythology. University of California Press., who says that he dwells in a heavenly hall called Glitnir, and all those who come to him with suits are soon reconciled. The Forseti cult was very likely brought to the Faroe Islands and Scandinavia, from Frisia. In support of this idea, we can consider the likely connection to the Amber trade between Frisians and Greek sailors, which was described by the Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia, (Kuhn 1968)4Iv. heldensage und heldendichtung. (n.d.). Aufsätze Aus Den Jahren 1968-1976, 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110838503-004 as well as the theory put forth by Grimm in Teutonic Mythology in 18825Grimm, J. (n.d.). Teutonic mythology … translated from the fourth edition with Notes and appendix by J.S. Stallybrass. London, 1900, 1883-88., that Fosite is the earlier usage, by linguistic analysis.

Ingwine Heathen Guidance

It would seem then, that Fosite is a god of law, of social order and reconciliation, who may (based upon the tale of the lawgivers and King Karl, and upon the Poseidon connection) additionally grant his auspices on those who find themselves lost at sea, or in need of guidance, real or metaphorical.