| Alternate Names: | Helio, Heil, Helið |

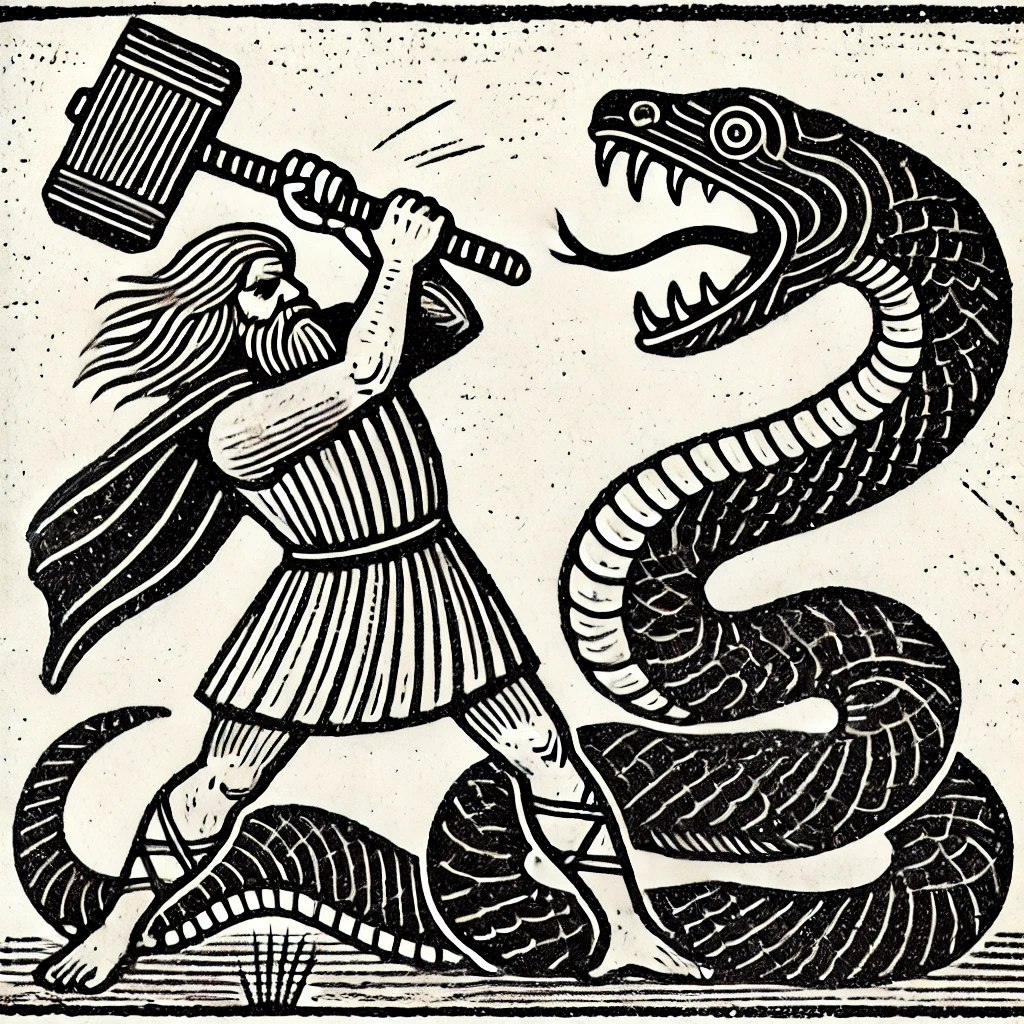

| Iconography: | A hero with a staff or club |

| Domains: | Healing, Prosperity |

Historical Attestation

Perhaps the most enigmatic of all the Gods of England, is that divine known variously as Heith, Helio, or Helið. The attestations to this God are quite obscure, and what lore survives must be deduced from the entirely Christian perspective of those who chronicled this deity and his cult in what is now called Cerne-Abbas in England. An 11th century account by the monk Gotselin tells us1Gotselin, Liba Major de Vita S. Augustini, Saeculum, I., fol., Paris, 1668.:

IBI PLEBS IMPIA TENEBRIS SUIS EXCAECATA, ET DIVINAM LUCEM EXOSA, NON SOLUM AUDIRE NEQUIBAT VIVIFICA IBI PLEBS IMPIA TENEBRIS SUIS EXCAECATA, ET DIVINAM LUCEM EXOSA, NON SOLUM AUDIRE NEQUIBAT VIVIFICA DOCUMENTA, VERUM TOTA LUDIBRIORUM ET OPPROBRIORUM TEMPESTATE IN SANCTOS DEI DEBACCHATA, LONGE PROTURBAT EOS AB OMNI POSSESSIONS SUA, NEE MANU PEPERCISSE CREDITUR ERFRENIS AUDACIA. AT DEI NUNTIUS JUXTA DOMINICUM PRAECEPTUM ET APOSTOLORUM EXEMPLUM, EXCUSSO ETIAM PULVERE PEDUM IN EOS, DIGNAM SUIS MENTIS SENTENTIAM, NON MALEDICENTIS VOTO, QUI OMNIUM SALUTEM OPTABAT, SED DIVINO JUDICIO, ET HELIAE TYPO ATROCIBUS INJECIT : QUATENUS SANCTORUM CONTEMPTORES TARN IN IPSIS QUAM IN OMNIBUS POSTERIS SUIS DEBETA PAENA REDARGUERET, QUI VITAE MANDATA REPULISSENT. FAMA EST ILLOS EFFULMINANDOS PROMINENTES MARINORUM PISCIUM CAUDAS SANCTIS APPENDISSE ; ET ILLIS QUIDEM GLORIAM SEMPITERNAM PEPERISSE, IN SE VERO IGNOMINIAM PERENNEM RETORSISSE, UT HOC DEDECUS DEGENERANTI GENERI, NON INNOCENTI ET GENEROSAE IMPUTATUR PATRIAE.

Here the sinful people dazzled themselves by darkness, and hate the divine light, not only in what is spoken, but also in what is written. Truth was totally ridiculed and God’s Saints were scorned and were booed. They took away all their property and inheritance, no hand or idea was saved. But the news of god’s commandment and the example of the apostles, who shook off the dust of their feet against them, because they were worth their punishment, yet they were not injured, because they wished them all salvation and they were consigned to the divine judgment, so that Helio (Helia) and his followers irrespective of their holiness would know the scope of their penalty, both for themselves as for their posterity, because of their rejection of the precepts of life. And it is said that they who came out of water by the fish, were desirous for sanctity and they have received now eternal holiness, because they were able to dispose themselves from the permanent stigma, in spite of the fight which they were imposed of by the country who rejected frankness and generosity.

This is a reference to an apparent visit of St. Augustine to the county of Dorset to preach the new religion, at the behest of Pope Gregory. Augustine was a Benedictine monk, who would one day become the first Archbishop of Canterbury. He was dispatched on this “Gregorian mission” with the explicit goal of converting Æthelberht, King of Kent, and by extension all his folk, from Heathendom to Christianity.

Augustine arrived in the district some time in the 6th Century, and began his efforts at proselytizing, whereupon the locals proceeded to mock and jeer, driving him and his delegation from the settlement in a humiliating fashion. There follows a doubtful tale of Augustine, some distance away from his initial defeat, striking the ground with his staff after seeing a vision of Christ, and causing a stream to bubble up, slaking the thirst of the demoralized monk and his retinue. He later returns, and smashes or otherwise destroys the idol, declaring a symbolic victory for Christendom.

Perhaps using these very writings of Gotselin as a source, the poet John Leland, writing much later says this in the anthology Joannis Lelandi Antiquarii de Rebus Britannicis Collectanea2Leland, J., Hearne, T., & Burghers, M. (1715). Joannis lelandi antiquarii de rebus Britannicis Collectanea. e theatro Sheldoniano., concerning the same story:

DEUS HELITH COLEBATUR IN PAGO DE CERNEL, TEMPORE AUGUSTINI, ANGLORUM APOSTOLI,

The god Helith was worshiped in the village of Cernel in the time of Augustine, apostle of the English.

So, who was this Helith? The etymology of the name is uncertain, but contrary to some recent interpretations, it seems somewhat certain from both context and a cursory linguistic analysis, that this is a reference to a masculine God, not a Goddess. Firstly, the only pronouns used in connection with this deity are masculine, e.g. “his”. Secondly, the Latin deus is also gendered, a goddess would be referred to as dea. Moreover, Helia, as an Old English proper noun would be masculine, as would derivations of OE heleþ or OS helið, both meaning (‘hero’), which is one of the offered etymologies.

Recorded considerably later than both of these attestations, is an interesting reference to the so-called “Cern God” by the English historian William Camden, who says in his volume Britannia in 16073Camden, W., & Telle, R. (1639). Britannia: Sive florent. Regnorum Angliae, Scotiae, Hiberniae … Descriptio. Blaeu., concerning Augustine:

…when he had dash’d to peices the Idol of the Pagan Saxons there, call’d Heil,

While the original here is Latin, the word Heil is Middle English, and would have been in use in the not-too-distant past, at the time that Camden wrote. This word would have derived from OE hǽl, meaning (‘omen, auspice, or good health’). If indeed this term is related, then perhaps what the missionaries heard as “Helia” was in fact “Hǽla”, a properly constructed Old English word which is present in Bosworth-Toller, but without a clear definition. It is certain that hǽl andheleþ are etymologically related and could imply martial prowess, protection, luck, healing, holiness, or all of the above. Given all this, a picture begins to emerge. One final piece of the puzzle to drop into place is an obscure (and admittedly quite late) reference by English churchman and scholar, Thomas Fuller. He writes in The History of the Worthies of England Vol. II, published in 18404Fuller, T., Nuttall, P. A., & Tegg, T. (1840). The history of the Worthies of England. Tegg.:

There is an obscure village in this county, near St. Neots,

called Haile-weston, whose very name soundeth something

of sanativeness therein ; so much may the adding of what

is no letter, alter the meaning of a word ; for, 1 , Aile signifieth

a sore or hurt, with complaining, the effect thereof. 2. Haile

(having an affinity with Heile, the Saxon idol for Esculapius)

importeth a cure, or medicine to a malady.

Now in the aforesaid village there be two fountain-lets,

which are not far asunder: 1. One sweet, conceived good

to help the dimness of the eyes : 2. The other in a

manner salt, esteemed sovereign against the scabs and leprosy.

What saith St. James ; “Doth a fountain send forth at the same

place sweet water and bitter?” || meaning in an ordinary way,

without miracle. Now although these different waters flow

from several fountains; yet, seeing they are so near together,

it may justly be advanced to the reputation of a wonder.

Esculapius, as may already be known to the reader, is the Roman god of medicine, whose serpent-entwined staff is commonly used as a symbol of medicine. Which brings us back to the tale of Augustine, and his “miraculous” spring. Is this a case of the Church appropriating an already existing wonder for the purposes of religious assimilation? It seems possible, even likely, in the estimation of the author. Fuller, a clergyman himself, makes the association of Helith/Heile with the healing springs in a completely different shire in England, without even the pretense of linking the potency of the spring to Jesus Christ (typically the first place a churchman looks in terms of rationalizing wonders). So it seems this is a second connection of the “idol” with healing, and with healing springs particularly. One might cautiously accept this as evidence that the worship of this God was not necessarily localized to Cerne-Abbas, but more broadly across Great Britain.

Ingwine Heathen Guidance

While this author has of necessity made a number of logical leaps with regard to the cited attestations of Helith, it nonetheless seems agreeable to advance the notion of Helith/Helia/Haile as an Anglo-Saxon God of healing and good fortune, and proceed to explore a possible relationship based on this groundwork.