| Alternate Names: | Erce, Folde, Eorþe, Nerthus, Fira Modor, Eorþan Modor, Hluþana, Hluθena |

| Iconography: | Oxen, Wagon, Tree, Pool, Wreaths, Snakes, A Bowl or Cup |

| Domains: | Earth, Fertility, Life, Success |

Table of Contents

Historical Attestation

Heathen spirituality, rooted in ancient Germanic traditions, places a profound significance on the natural world and its interconnectedness. Central to this worldview is the veneration of Mother Earth, known as “Jord” or “Fjörgyn” in Old Norse, or “Eorþe” in Old English. She is also called Fira Modor, the “Mother of the Living”. In our Heathenship, Mother Earth is revered as a powerful and nurturing force, embodying both the physical and spiritual aspects of nature. She is seen as the source of life, sustenance, and abundance, representing the cycles of birth, growth, death, and regeneration. Heathens recognize that their existence is intricately woven into the intricate web of nature, and they strive to foster a deep reverence for the Earth, emphasizing a reciprocal relationship with the land and its creatures. By honoring and protecting Mother Earth, Heathens seek to maintain harmony and balance within themselves and the wider world, understanding that their actions have consequences that reverberate throughout the natural order. This sacred connection to the Earth forms the foundation of Heathen spirituality, encouraging a profound sense of stewardship and a profound understanding of the intrinsic value and interdependence of all life. While Old English literature does not say much directly concerning this most ancient of goddesses, very much indeed can be inferred, after careful examination of the sources.

One of the earliest sources we have which indicates the reverence in which the Angles in particular held Mother Earth, comes from the Roman chronicler, Cornelius Tacitus tells us in his work, “Germania”:

The Langobardi are distinguished by being few in number. Surrounded by many mighty peoples

they have protected themselves not by submissiveness, but by battle and boldness. Next to them come

the Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarines and Huitones protected by rivers and forests.

There is nothing especially noteworthy about these states individually, but they are distinguished by a

common worship of Nerthus, that is, Mother Earth, and believe she intervenes in human affairs and

rides through their peoples. There is a sacred grove on an island of the Ocean, in which there is a

consecrated chariot draped with a cloth, which the priest alone may touch. He perceives the presence

of the goddess in the innermost shrine and with great reverence escorts her in her chariot, which is

drawn by female cattle. There are days of rejoicing then and the countryside celebrates the festival,

wherever she deigns to visit and to accept hospitality. No one goes to war, no one takes up arms. All

objects of iron are locked away then and only then do they exercise peace and quiet, only then do they

prize them, until the goddess has had her fill of society, and the priest brings her back to the temple.

Afterwards the chariot, the cloth, and if one may believe it, the deity herself are washed in a hidden

lake. The slaves who perform this office are immediately afterwards swallowed up in the same lake.

Hence arises dread of the mysterious, and piety, which keeps them ignorant of what only those who

are about to perish may see.

This seems to align well with later pieces of evidence, such as the so-called Old English field Remedy, or “Æcerbot”, an Old English metrical charm that provides prayers and rituals for the blessing of fields that are not yielding well. It is believed to have been written down in the 10th century and is preserved in the Exeter Book.

The text includes a series of prayers and blessings, as well as instructions for performing various rituals, such as the sprinkling of holy water and the marking of boundaries. The focus of the Æcerbot is on ensuring the fertility and productivity of the land and crops, which is consistent with pagan agricultural rites.

While the Æcerbot is considered by some to be a Christian text, it likely has roots in earlier pagan traditions. The emphasis on the fertility of the land and the use of ritual and blessings to ensure a successful harvest are elements that are common to many pre-Christian agricultural rites. Additionally, the inclusion of references to pagan deities, such as Erce and the Four Corners, suggests that the Æcerbot may have been influenced by older pagan beliefs and practices. It is in this charm, that we see the ritual cry, Erce, Erce, Erce, eorþan modor, or “Erce, Erce, Erce, Earthen Mother”, which has a great formulaic similarity to other traditional chants found in the written sources, such as “Wôld, Wôld, Wôld!” to invoke Woden, or “Friggöu, Friggöu, Friggöu!” to invoke Frig. This seems to be such a close correspondence, that this author feels it can be posited with some certainty, that this is indeed a chant of a proper noun, that the linguistically difficult-to-parse “Erce” is indeed an Old English name for the “Earthen Mother”. This phrase has been read to mean “The Mother of Earth” causing some consternation among Anglo-Saxoninsts, but can also be read simply as the “Mother (comprised of) the Earth” [sic] where “Earth” takes the genitive to indicate it exerts a qualitative “of” connection to “Mother”, as in the phrase “earthen pot”. This does not mean that it refers to the mother of the Earth Goddess. She is also personified in this same charm as Fira Modor (“Mother of the Living”) and as Folde, (“The ground”).

Identification as Hludana and the Mother of Thur

As we explore the lore of Eorþe, we must concede that her name and identity is incontrovertibly cognate to that of the Norse earth goddess, Jǫrð. It is also important to note, that Jǫrð is almost universally accepted to be one and the same as the goddess Hlóðyn. In stanza 55 of Völuspá, Thor is called “the mighty son of Hlóðyn.” The same connection is made between Thor and Jǫrð.

The etymology of Hlóðyn is problematic in Old Norse, potentially because the Hlóð- component is difficult to explain, and some proposed solutions, such as one which has the name deriving from ON Hlað-, (“to lade with cargo”) do not bear up well under close scrutiny. It is more likely in this author’s opinion, that that just as Jǫrð and Hlóðyn are two aspects of the same goddess, we must consider that our Eorþe is one and the same as the Germanic goddess, Hluθena, whose name would be pronounced almost exactly like “Hlóðyn”, or as she is more commonly known, Hludana.

Hludana is potentially one of the most important of the goddesses of Germania Inferior in the Migration Age, but much of her lore has been lost, leading to a difficult reconstruction.

The notable Austrian philologist, Siegfried Gutenbrunner notes in his 1936 book Die germanischen Götternamen der antiken Inschriften, that the name Hludana is composed of two parts: hluda, which means “loud” or “resounding”, and -ana, which is a suffix that can mean “goddess” or “divine person”. Reviewing this etymology, we find that indeed our word “loud” derives from Old English hlud, and before that, Proto-West Germanic *hlūd, which can mean both loud in the sense of sound, as well as “famous”. Speaking to the issue of the difficult etymology of Norse Hlóðyn, it seems that this exact derivative of the Proto-Germanic *hlūdaz, (“loud/famous”) did not survive into Old Norse, which would in a sense make Hlóðyn a sort of loan word. The Latinized Germanic ending -ana conceptually aligns with the Norse suffix -yn used in the same way in “Hlóðyn” and “Fjorgyn”. However, Hlóð- means nothing in Old Norse. There is no intelligible Norse meaning perhaps because direct descendants of Proto-Germanic *hlūdaz survive only in West Germanic languages, there is no direct Norse cognate. Linguist Walther Khun suggests the name Hludana is, via the ultimate Indo-European ancestor word *ḱlew, closely related to Old Greek κλυδων and κλυδωνα (kludoon(a) “high waves, rough water”) I suggest here, that Hlóðyn literally means “Hludana” in Old Norse, leading to the (fairly) widely accepted conclusion that the one goddess is indeed a Nordic “version” of the other, as was suggested by scholars such as Jan deVries and Jacob Grimm. If accepted, this would make Hludana the sometime consort of Woden, co-wife of Frig, and mother of Thur; a goddess of the untamed seas, stormy weather and the Earth, who having mated with the furious sky god, bears a child, the god of thunder.

It has been argued that this name suggests that Hludana was a goddess associated with loud or resounding events, such as the aforementioned storms, or the cries of childbirth. Gutenbrunner also notes that several of the inscriptions that mention Hludana come from military contexts, suggesting a connection to protection, if not necessarily war. For example, one inscription found in Germany reads:

Dea Hludana, quem L. Plotius firmus mil(es) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito)

To the goddess Hludana, whom Lucius Plotius Firmus, soldier, fulfilled a vow willingly and deservedly

This inscription, along with others like it, suggests that Hludana was worshipped by soldiers and may have been seen as a protector of warriors. On the other hand, an inscription found near Beetgum reads:

DEAE HLUDANAE CONDUCTORS PISCATUS MANCIPE Q (UINTO) VALERIO SECUNDO V (OTUM) S (OLVERUNT) L (IBENTES) M (ERITO)

To the goddess Hludana, the fishing contractors, when Quintus Valerius Secundus acted as tenant, fulfilled their vow willingly and deservedly.

This would seem to imply she was also viewed as having influence over fishing, and perhaps, prosperity and abundance in general. In his work Teutonic Mythology, Jacob Grimm suggests that Hludana may have been the goddess of the Anglo-Saxon month corresponding to March, Hlydmonath, which he translates as “the month of loud, i.e., stormy weather,” and that she may have been associated with storms and birds, as alluded to above. However, he also notes that this theory is speculative and that there is no direct evidence to support it (see: Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology, Vol. 1. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. Dover Publications, 2004).

What we know of her iconography and what it might say about her realms of influence from a purely historical perspective, is highly speculative. What we do know mostly comes from the area of the modern city of Trier in Germany. The city was an important Roman settlement during the time of the Roman Empire, and it is believed that the Romans adopted some of the local deities and incorporated them into their own religious practices.

In Trier, there is an ancient inscription on a stone slab that mentions a goddess named Hludana. The inscription was discovered in the late 19th century in the district of Olewig in Trier, and it is believed to date back to the 2nd or 3rd century CE. The inscription reads as follows:

DEAE HLVDANAE SACRVM CVRANTE FLAVIO AVR[ELIO] POTENTE,

Sacred to the goddess Hludana, under the care of Flavius Aurelius Potens.

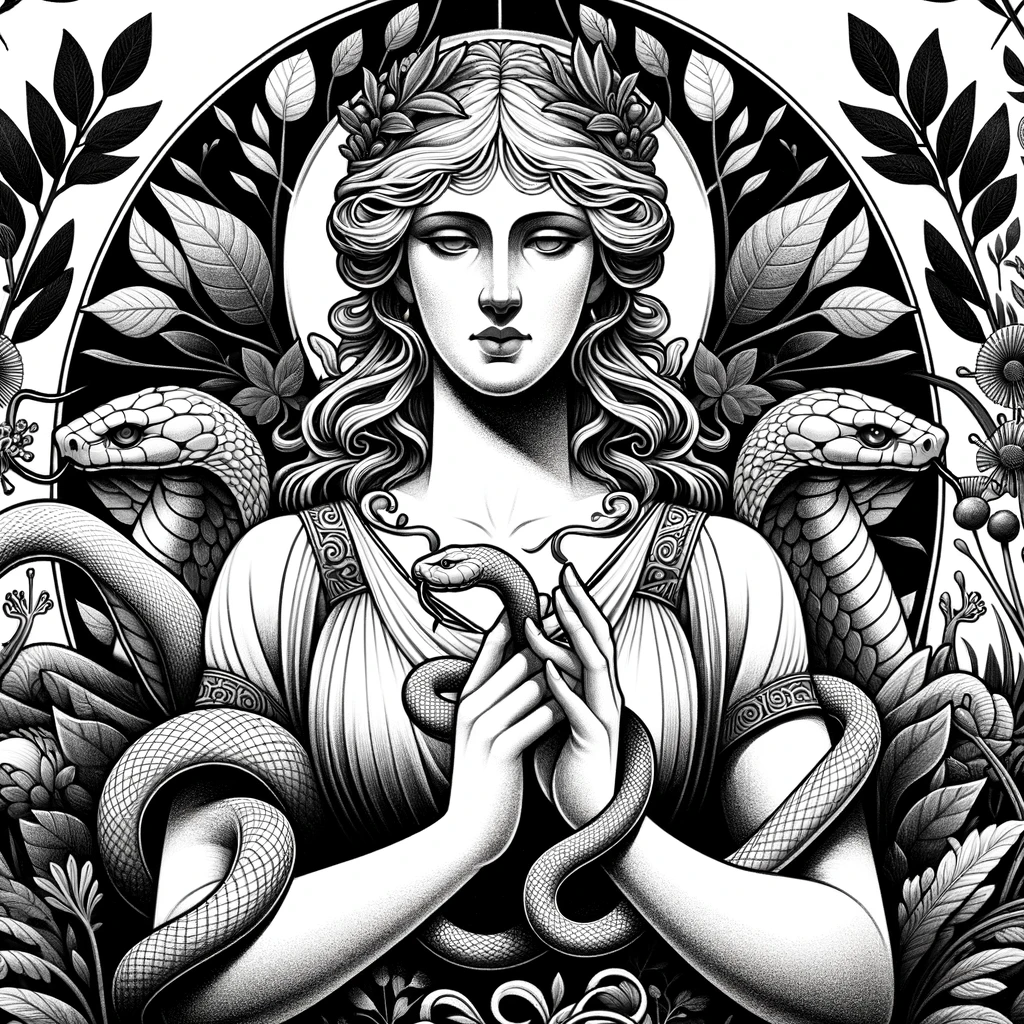

There are also other inscriptions and artifacts found in the Trier region that suggest the worship of a goddess that some regard as Hludana, including a stone relief that depicts a goddess holding a wreath and a snake, which may be a representation of Hludana. Snakes have a long-standing association with the magical world, with wisdom, and with rebirth. Wreaths also carry a fairly well understood symbolism in European culture, that of victory. These symbols are perhaps signals of the areas in which Hludana was thought to wield dominion. Some writers have put forth a connection of Hludana with love and fertility. Philologist Jan de Vries discusses the possible associations of Hludana with both snakes and with love, stating:

Die Schlange könnte das Symboltier der Hludana gewesen sein, weil das Wort slange [Schlange] lautlich mit hlúd [laut] verwandt ist. Hludana wäre somit sowohl als Liebesgöttin, deren Hauptheiligtum sich in Trier befand, als auch als Göttin der Schlange, die im Trierer Bezirk verehrt wurde, zu betrachten.

The snake could have been the symbol animal of Hludana, because the word ‘slange’ [snake] is phonetically related to ‘hlúd’ [loud]. Hludana could thus be regarded both as a goddess of love, whose main sanctuary was located in Trier, and as a goddess of the snake, which was venerated in the Trier district.”–de Vries, Jan. Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, Vol. 1-2. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1956-1957

One example of an artifact with snake motifs that may be connected to Hludana is the bronze votive plaque found at the Trier-Nord industrial estate in Germany. The plaque depicts a woman holding a snake in each hand and has been interpreted as a representation of the goddess Hludana.

Another example is a small bronze figurine found in the Moselle River near Trier, which depicts a woman holding a snake in her right hand and a cup in her left. The figurine has been dated to the 2nd or 3rd century AD and is thought to be a representation of a local deity, possibly Hludana.

Other artifacts with snake motifs found in the region of Trier include brooches, fibulae, and other small metal objects. While these objects do not necessarily depict Hludana specifically, their presence in the same area as other Hludana-related artifacts suggests a possible connection. The imagery on the artefacts described above calls to mind the so called “Snake-witch stone” or Smisstenen, that was discovered in När socken, Gotland, Sweden. Various explanations for the symbol on the stone have been put forth, most are in this author’s considered opinion, uncompelling in the extreme. Some theories connect the figure to a snake goddess from Crete, or even with biblical figures, but these theories are very difficult to support. Attempts to connect the witch or goddess to an Icelandic figure have also largely been fruitless. The stone has been dated to 400–600 CE, which places it within the Migration Age, might not this figure be a representation of Hludana? While entirely speculative, this explanation seems as plausible, if not more plausible than any yet proposed. Gotland is certainly within reach of traders from Frisia, who we know to have traded and interacted with other peoples in the North Sea surround, and Scandinavia.

Some scholars, such as DeVries and Rudolf Simek, feel that a case can be made that she was worshipped at least in part as a goddess of wisdom and prophesy. In his book Dictionary of Northern Mythology, scholar Rudolf Simek briefly mentions Hludana in the context of discussing the goddesses of Germanic mythology. Simek notes:

Inscriptions to Hludana are known primarily from the Trier region. They suggest that she may have been a goddess of divination or prophecy. Small figurines or other offerings found at the sites of her cult may have been made to obtain guidance or information.— R Simek, 1996, p. 155

Additionally, the Goddess has been tentatively associated with healing, some scholars have suggested, based in large part on her associations with water and possibly with snakes. Water was often associated with healing in ancient cultures, and many goddesses of healing or medicine were associated with bodies of water such as rivers or springs. Snakes were also sometimes associated with healing or with the underworld, and some goddesses of healing were depicted holding snakes or accompanied by them. The Beetgum votive stone mentioned above explicitly connects Hludana with fishing, and in the view of many, water. Thus this association seems entirely plausible as well. Certainly the Anglo-Saxons associated the snake or wyrm both with disease, and with the curing of disease, providing a strong West Germanic connection of serpent motifs, to the art of healing (Ball, 2017).

While the serpent in mythology has long been connected in the eyes of many indigenous peoples worldwide with wisdom, rebirth, and medicine, the connection made above by DeVries of the snake with ‘love’, is a bit more difficult to parse. Certainly, snakes are phallic in appearance and bear many young, so a connection to fecundity and sexuality can perhaps be made. It may make more sense if we view this connection in a broader context of fertility, rather than purely romantic love. While there is no broad academic consensus in this matter, there is some support among scholars for this view. In her book Matronae et Matrones: A Study of the Matron Cult in Roman Germany in 1989, scholar A. J. Barnard suggests that Hludana may have been a fertility goddess based on the fact that some inscriptions to her mention offerings of grain or fruit, which were often associated with agricultural fertility. While H. R. Ellis Davidson feels that due the connotations of fame or renown attached to the term hlúd, that she may have been viewed as promoting fertility or abundance (Davidson, 1964). It would seem then, that her historical portfolio was perhaps quite broad, involving both war and peace, sexuality and abundance. This invites comparison with other Germanic goddesses such as the Norse Freyja, and indeed, in the article “Fertility and the Transformation of Society: The Goddess Frigg and Her Associates,” Stefan Zimmer notes that:

In the Trier region, a goddess called Hludana was worshipped, whose name and function suggest a possible association with the Germanic concept of frith. She may have been responsible for the fertility of the land and the prosperity of the people, a role that is similar to that of the Norse goddess Freyja.–Zimmer, Stefan. “Fertility and the Transformation of Society: The Goddess Frigg and Her Associates.” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 23 (1989): 327-348.

While these goddesses are assumed to be separate entities, within their respective cultural contexts, it is worth noting that scholars have made the comparison, as it demonstrates these various functions co-existing in a single Germanic goddess, both of whom seem to have been held in very great regard.

Ingwine Guidance

Now let us turn to interpreting the lore of this goddess for the modern practitioner. In the tradition of Ingwine Heathenship, Hludana is viewed as a chthonic goddess, with connections to the cycle of life, death and rebirth. She is a goddess of prophesy, wisdom, healing, and good fortune in agriculture and fishing. She is also importantly, connected with protection in battle and the establishment and protection of social order. She is seen as a goddess that has dominion over romantic love, fertility, and general abundance. She is associated with snakes and with water, and perhaps also the cow, or the wagon, and may be particularly called upon for aid in enterprises that happen on or near water. She is also called upon in her guise as Folde, Erce, or Eorþe, in matters of horticulture and farming, as these names seem to refer to her more “domestic” side, while Hludana is perhaps, inherently wild and tempestuous. She is the consort of Woden, and the mother of the mighty thunder god, Thur/Thunor.