| Alternate names: | Wodan, UUoden, Godan, Weda |

| Iconography: | Eye Motif, Man with Horned Helmet, Man with hounds, Ravens |

| Domains: | War, Healing, Sex, Magic, Abundance (Harvest), Death |

Table of Contents

Woden historically held a place of honor among the gods of the West Germanic peoples, particularly the Saxons. This continues to be the case in the present day. He is revered by many Heathens as the foremost, or among the foremost, of all the gods. His name means (‘furious’) or possibly (‘Wind’), and likely comes from the Proto-Germanic Wōđinaz, though this is not directly attested. This is likely a reference not only to his association with actual meteorological events, but also metaphorically speaking to ecstatic states, such as trance, or battle-frenzy. In Old Norse he is Óðinn, (an exact cognate) and though many modern Anglophones render that name as Odin, (pronounced /ˈoʊdɪn/), this a modern pronunciation found typically only in the United States and other primarily English speaking nations. He is the husband of Frig.

Historical Attestation

Due to his connection with matters of the spirit and the esoteric, he is associated by Latin scholars of antiquity with the Roman god Mercurius, in the tradition of Interpretatio Romana in which the name of a Germanic god is glossed by a more familiar (to the glossator) Roman one.

Woden is often represented as wearing a hat and cloak, bearing a spear, and accompanied by two ravens, “Thought” and “Memory”. These ravens, themselves omens of death in the eyes of many, fly out across the wide world, observing and bearing news to their master. In folklore, Woden is often associated with Ravens generally, as they are carrion birds (OE Néfuglas) and thus connected with the aftermath of battle.

Regarding his prominence in Heathen religion, English antiquarian Aylett Sammes says in 1676 in his Britannia Antiqua Illustrata1Sammes, A. (1676). Britannia Antiqua Illustrata: Or, the antiquities of ancient Britain, derived from the Phoenicians wherein the original trade of this island is discovered: Together with a chronological history of this kingdom, from the first traditional beginning until the year of our lord 800. :

WHAT strange and monstrous Opinions the Saxons conceived of WODEN, may be gathered out of most of their Authors, who seldom mention his Name without some excessive Encomium of his Person, or miraculous relation of his Magical performances, whether it were that in those Ages the pretending to supernatural assistances was indispensably necessary to the Conducting of People from their own Countries, and establishing them in New ones, or whether Woden was no more than an ordinary Leader, and his Actions made miraculous after his death, certain it is, none of all the Saxon Nation ever attained to so great Reputation, being worshipped in all places, and by all Sexes, and saluted with the highest title of Divinity, Den almegiste aas, and hin almatke aas.

Here, he alludes to a byname of Woden, “The All-Mighty As”, the chieftain of the Gods. Woden was seen not only as chief among divinities, but also a founder of ruling dynasties among humans. The venerable Bede tells us of the Saxon invasion of the British Isles2Bede, Colgrave, B., McClure, J., & Collins, R. (2008). The ecclesiastical history of the English people. Oxford University Press.:

The two first commanders are said to have been Hengest and Horsa … They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vecta, son of Woden.

Indeed, the royal genealogy of the ruling house of Wessex traced its lineage to the god as a source of legitimacy, and while later scribes amended this and other royal genealogies to insert biblical figures such as Noah or Adam ahead of Woden, his name remains in the official lineage of the monarch of Great Britain, to this day. Having been credited with Siring a number of royal houses among the West Germanic peoples, he is in a very meaningful sense the “All Father”, as he is sometimes called. A progenitor of nations.

So, besides the art of rulership and the creation of rulers, what does this mighty god’s portfolio include? Sammes goes on to say:

…Besides this, he had a way to call up the Ghosts of deceased Persons, and at his pleasure shut them up in Hills and Rocks, whence he was called Dronga Drotten, and hon∣ga Drotten, Lord of the Hobgoblins

While the term “hobgoblin” is less than artful, (undead would be a better translation) this does tell us something of the character of Woden. We can deduce from this that he is a psychopomp, a caretaker of the spirits of the dead. This is born out in later Norse mythology, where it is said of the home of Óðinn:

The fifth is Glathsheim, | and gold-bright there

Stands Valhall stretching wide;

And there does Othin | each day choose

The men who have fallen in fight.Easy is it to know | for him who to Othin

Comes and beholds the hall;

Its rafters are spears, | with shields is it roofed,

On its benches are breastplates strewn.The Poetic Edda, translation by Henry Adams Bellows, [1936]

These passages concerning Óðinn must be evaluated in context, as coming from a later era than the Anglo-Saxon period, and they certainly are colored by the economic, and cultural and military pressures of the Viking Age. Nonethless, if viewed purely from a thematic standpoint, they would possibly corroborate Woden’s role as a warden of the dead, and particularly those who die in battle. His followers include female furies known as Valkyries, (OE wælcyrgan) who are the “Choosers of the Slain”, riding sometimes invisibly among warriors on the battlefield, granting victory to some, death to others. It is said specifically of Óðinn that he seeks to gather the undead spirits of the greatest warriors in Corpse-Hall (ON ‘Valhǫll ‘) in preparation for a final conflict with the forces of Chaos, though we have no (surviving) attestation of the concept of Ragnarok in Anglo-Saxon sources. Neither do we have a direct reference to a heavenly dwelling known as Corpse-Hall. We do see however, oblique references in old English literature to a ’ Winehall of the proud’ or wlancra winsele, Mentioned in connection with the afterlife. It is entirely probable that early Germanic peoples already had a notion that great warriors would dwell together in fellowship after death.

Further attestations to the character of Woden as a god of battle and victory, can be seen in the Origo Gentis Langobardorum, or (‘Origin of the Lombard People’). In this 7th Century legend, a small tribe known as the Winnili, had left their original homeland in Scandinavia. They found themselves falling afoul of the Vandals, a larger and more powerful tribe who dwelt in a land called Scoringa, which some scholars assume to be a region on the banks of the Elbe River. The Vandals, seeing how they outnumbered the newcomers, demanded tribute. The Winnili, feeling it was better to live free or die, instead offered battle, and sought the auspices of Godan (Woden) in the looming confrontation. Godan, it is said, told the Winnili he would grant victory to the first army he saw on the field in the morning. Presumably at the same time, the ranking lady among the Winnili, one Gambara, sought the aid of Frea (Frig) in the cause of the Winnili. The goddess told Gambara to have all the women of the tribe tie their long hair in front of their faces, and join the outnumbered men in battle. She then spun Godan’s bed during the night, so that he faced the host of the Winnili when he arose. Seeing the women among the men, and perceiving their hair as beards, he asked his wife, “Who are these long-beards?,” and Frea replied, “My lord, thou hast given them the name, now give them also the victory.”

This he did, and thereafter, the Winnili were known as the Langobards, or Lombards, “Long-Beards”.

It should be noted, that while the martial tone of the depictions of Norse Óðinn and the Godan of the Langobards is only partially born out in attestations of the Anglo-Saxon Woden, it does seem clear he was viewed as a god who took an interest in both armed conflict, and in the liminal space between the world of the Living and dead. He is indisputably a god of combat and warlike arts, and this warlike demeanor was already seen in tales concerning Woden well prior to the Viking Age, as in the above cited story from Origo Gentis Langobardorum. On the shores of the Frisians, who were themselves Ingvaeones like the Anglo-Saxons, we see recounted in the journals of several German antiquarians, tales of a celebration that was alleged to take place on the eve of February the 22nd. We are told by historian Niels Nikolaus Falck3Archiv für Geschichte, Statistik, Kunde der Verwaltung und Landesrechte der Herzogthümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg Volume 4:

On the day of St. Peter in Cathedra (Feb 22) a great festival was formerly held in North Friesland. It was a spring festival; for then the mariners left the shore and put out to sea. On the eve of the above-mentioned day great fires (Biiken) were lighted on certain hills, and all then, with their wives and sweethearts, danced around the flames, every dancer holding in his hand a wisp of burning straw, which he swung about, crying all the time: “Wedke teare!” or “Vike tare!” (Wedke, i.e. Woden, consume!). That is, consume (accept) the offerings, as in the days of heathenism.

It would seem that this sacrifice was intended to secure victory in the upcoming adventures upon which the men would soon be embarking, as the weather became more clement. This would seem to cement in place the notion of Woden as a patron god of victory and daring, as is certainly seen to be the case in North and Elbe-Germanic sources.

It is likewise agreeable, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, to attribute to Woden those aspects of his Norse counterpart that deal with inspiration, and the ability to enter ecstatic states for the purpose of shamanic work, or the seeking of wisdom. It is likely that the mythological motif of Óðinn/Woden sacrificing “himself to himself” by hanging on a tree is indeed a reference to the god passing through a liminal state into the Underworld, to seek the knowledge that could only be found in this altered state, “dead” but not dead. Indeed, one recorded byname for Óðinn is Hangi, the Hanged God, and another is Heimþinguðr hanga, (‘visitor of the hanged’) in reference to his ability to make the dead reveal their secrets.

It seems only natural that this connection of Woden to death, and the realm of the Dead, would extend into a broader connection with the Otherworldly in general. He is frequently depicted traversing the land and the skies on a powerful magic horse, referred to in Old Norse literature as (Sleipnir ‘One who Slips’ ), possibly in reference to his ability to enter other planes of existence. While the steed of Woden is not explicitly named in Old English sources, one might translate it as Slíepere, but again it should be stressed this is a neologism. He is viewed by many as a shamanic figure, having sacrificed his eye to gain wisdom by casting it into the Well of Knowledge. While we do not have any written accounts in Old English or Frisian regarding his sacrificed eye, there is a wealth of Anglo-Saxon material culture substantiating the notion that Woden was seen at least during the latter part of the Migration Age, as one-eyed. One such data point exists in the form of so-called “Eye of Woden” amulets, depicting the god’s eye in a “well” and sometimes surrounded by, or entwined in a trefoil or four-cornered design. Other interesting examples of material culture alluding to the Eye of Woden exist as well, including one crafted into the now-famous Sutton Hoo helmet; the “eyebrow” pieces of the helmet are different, with one having a foil backing behind the the garnet ornamentation, that would have reflected light quite noticeably. The other eye has no such foil backing, and thus it would not have been as bright when viewed in firelight (Bruce-Mitford, 1978, 169). The wonderful paper entitled What Colour a God’s Eyes4Mortimer, P. (2019, May 26). What colour a god’s eyes. http://blogg.mah.se/historiskastudier/bloggen/?fbclid=IwAR3HBy-Yl1X8dkFXZFebTXINenYRdkar9EkqRyLdfvA2TgxqpZFML8pL0Ho. https://www.academia.edu/39265823/What_Colour_a_Gods_Eyes by Paul Mortimer, elucidates well on the topic of Germanic (including West Germanic) artifacts that depict or seem to depict, a god with an altered eye, lending credence to the notion that Woden was well-known across many areas of Germanic-speaking Europe and Britain as having sacrificed one eye for esoteric wisdom.

It is worth mentioning at this point one type of uniquely Anglo-Saxon artifact that points to a widespread English cult of Woden, the WAINE, or Woden Avatar in Numerous Environments. These artifacts often depict a figure generally accepted to be Woden, a male figure with a double-terminated headdress. Interestingly, many show the god with two unaltered eyes, although as Mortimer rightly points out, he did of course originally have two, until sacrificing one. These ornaments are of ambiguous function, although it seems possible they were a form of personal jewelry, and in design are incredibly uniform. These artifacts have been unearthed only in England, and would seem to suggest the Cult of Woden was thriving even into the Seventh century.

Legends of his travels through this world and the Otherworld, seeking knowledge or upon other mysterious errands, may have contributed to his connection with the spectral “Wild Hunt”, a ghostly procession attested in Medieval times, and even into the early Modern Era. This frenzied procession of ghosts and elves was said to occur at the darkest and coldest point of the year, and the motif is to be found in the folklore of Scandinavia, Germany, England and elsewhere. To the Anglo-Saxons, this procession was sometimes called the Herlaþing, after its mysterious leader, King Herla, who is often stipulated by folklorists to be Woden in disguise. This myth in turn may have inspired the stories of Herne the Hunter, a specter said to haunt Windsor Forest. The exact provenance of this myth remains uncertain, but in the earliest written account of Herne, The Merry Wives of Windsor, the Bard himself writes5Shakespeare, W., & Greg, W. W. (1910). Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of windsor, 1602. Clarendon Press.:

There is an old tale goes, that Herne the Hunter

(sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest)

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age

This tale of Herne the Hunter for a truth.

It is also worth observing, that in some versions of the myth of Herne, he is said to have hung himself from “Herne’s Tree”, which may be of some interest, as the Norse mythology of Óðinn himself relates that in order to gain the power of the Runes, Óðinn had first to hang himself in a ritual of self-sacrifice. The connection between the two is admittedly tenuous, but nevertheless, the motif of the Wild Hunt does connect Woden with Herla, who seems to have quite possibly inspired Herne.

Having learned the power of the Runes, Woden is regarded as the father of writing both magical and mundane, and of language generally. we see in the Old English Rune Poem, in the stanza of the rune Ós:

ōs byþ ordfruma ǣlcre sprǣcewīsdōmes wraþu and wītena frōfur

and eorla gehwām ēadnys and tō hiht

god is the originator of all language

wisdom’s support and wise man’s comfort

and to every noble blessing and hope

It should be noted here, that while the word ós is most straightforwardly translated as ’god’, it is in fact a singular form of Ése, or in Old Norse, Æsir, A heathen God, and one who is quite often accepted to be Woden himself (Pollington, 2008)6Pollington, S. (2008). Rudiments of runelore. Anglo-Saxon Books..

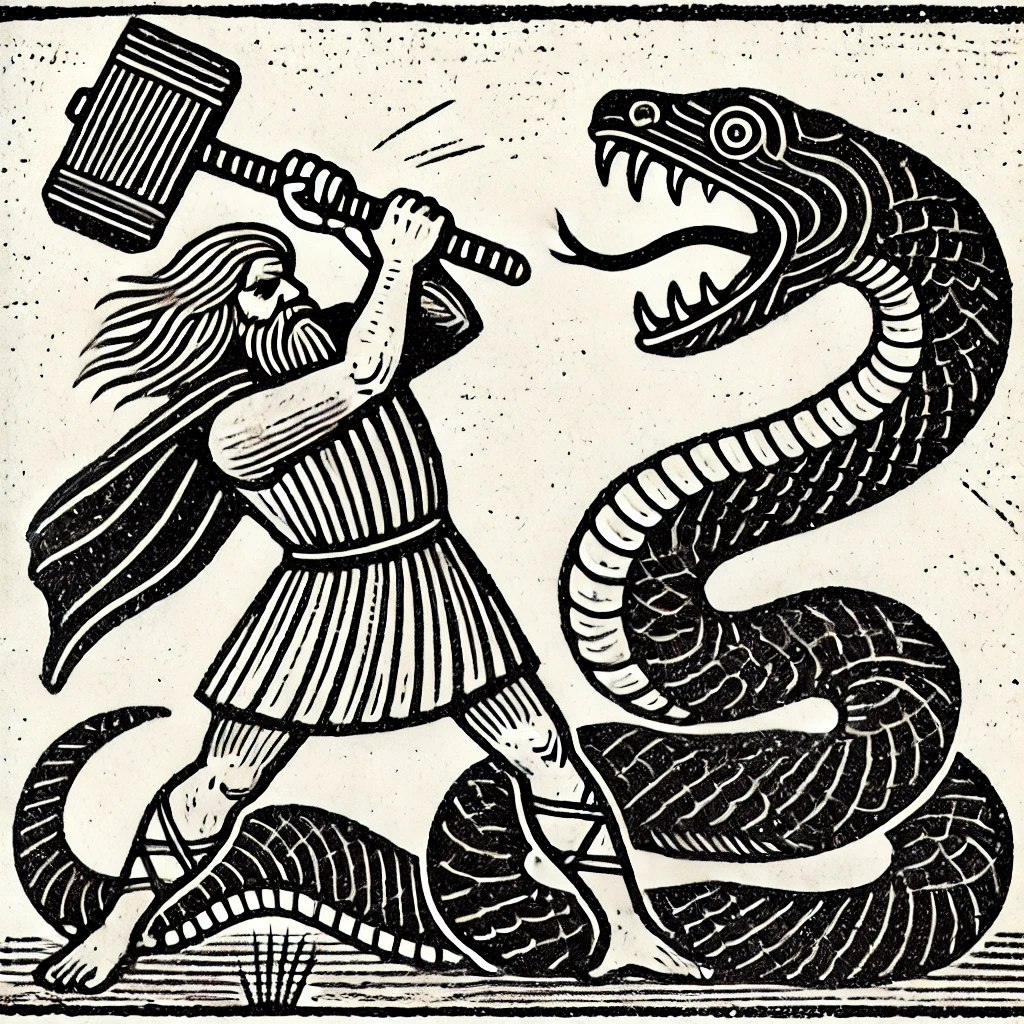

Woden is a master of galdor-cræft (‘enchantment’) and is said to have the secret of applying “battle-fetters” to entire armies, rendering them disordered and panic-stricken. Another chant he knows will release men from just such a spell. In addition to these war-like attributes however, Woden is also seen to use his magic for benevolent purposes, such as healing. In the fragmentary “Second Merseburg Charm”, it is written:

Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods,

and the foot of Balder’s foal was sprained

So Sinthgunt, Sunna’s sister, conjured it;

and Frija, Volla’s sister, conjured it;

and Wodan conjured it, as well he could:Like bone-sprain, so blood-sprain,

so joint-sprain:

Bone to bone, blood to blood,

joints to joints, so may they be glued.

Woden is similarly invoked in the Old English “Nine Herbs Charm”, as a master of healing magic, with knowledge of herbs and their magical properties. While this aspect of the Norse Óðinn is somewhat understated, it seems clear that the earlier Germanic conception of Woden was very much of a god of healing, wisdom, and indeed, a god to be invoked for a bountiful harvest.

In Medieval England, there existed traditions of marking the end of the grain harvest season, by leaving a single sheaf unharvested, sometimes called a neck or “Mell”, a term that leant itself to the celebratory supper that would often follow. These traditions recall other Germanic Harvest rites, such as the one described in a commonly republished article on the web, that cites Jacob Grimm:

A celebrated late attestation of invocation of Wodan in Germany dates to 1593, in Mecklenburg, where the formula Wode, Hale dynem Rosse nun Voder “Wodan, fetch now food for your horse” was spoken over the last sheaf of the harvest.

This indeed is related by Grimm in Teutonic Mythology (Grimm, 1835 Pg 156)7Grimm, J. (n.d.). Teutonic mythology … translated from the fourth edition with Notes and appendix by J.S. Stallybrass. London, 1900, 1883-88. as part of a ritual wherein mowers would leave the last sheaf of the rye harvest as a sacrifice to Woden— food for his horse. He goes on to write of a similar custom in Schaumburg that survived to within 50 years of his own writing. Mowers cutting corn offer libations to Wodan, and shout:

Wôld, Wôld, Wôld!

hävenhüne weit wat schüt,

jümm hei dal van häven süt.

Vulle kruken un sangen hät hei,

upen holte wässt (grows) manigerlei:

hei is nig barn un wert nig old.

Wôld, Wôld, Wôld!

Should this ritual be omitted, he writes,

…the next year will bring bad crops of hay and corn.

This would seem to attest to crop cultivation and harvesting as being with Woden’s portfolio. Even as late as the Poetic Edda, Oðinn is regarded as the sometime consort of Jörð, the Earth Mother, and father of the thunder god, Thor. This seems to speak to a “family business” of sorts! So in summary, what can we say of the portfolio of Woden?

Ingwine Heathen Guidance

Given the extant folklore from England, Germany, and Scandinavia, and taking into account Viking Age poetic evidence, it seems clear Woden is a war god, invoked for victory in battle, and interested in the outcome of conflicts between mortals. He is likewise interested in founding and nurturing civilizations, promoting social order, and might be seen as a patron of strategists, leaders, artists and scholars. He is in a very real sense, a god of kingship. He is seen by many as chief among the gods, a divine father metaphorically if not in some cases, literally.

Woden is a god with power over tempests and storms. A god of bountiful harvests, he is the father of the thunder god Thunor (the Anglo-Saxon counterpart to the Norse god Thor), the sometime lover of Hludana and the husband of Frīg. Journeying throughout the worlds on his mighty steed seeking understanding of all things, he is wise and knows much that is hidden. He might be approached for assistance with esoteric matters, and matters of the spirit. He possesses the gift of inspiration, and can be called upon by those seeking to enter trance-like or ecstatic states, or those who seek poetic or artistic inspiration. Among the gods he is a chieftain, priest, soothsayer and magic-user, with dominion over death and the dead, as well as healing and divination.