Hengist and Horsa are two figures that loom large in the mythos of early England. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and the writings of Geoffrey of Monmouth, to wit, Historia Regum Britanniae, these two warriors played a crucial role in the early days of the Anglo-Saxon invasion and settlement of Britain. While their exact historical significance is the subject of much debate, their legendary status as heroic conquerors has had a lasting impact on English folklore and tradition. Legend holds that Hengist and Horsa were the sons of Wihtgils, who was the son of Witta, who was the son of Woden.

The names of these heroes are themselves a subject of interest, and controversy . Their names derive from Old English words of Germanic provenance, meaning “stallion” and “horse,” respectively. This has led some scholars to speculate that these were nicknames of a sort, rather than true personal names.

The horse and horseman motif played a significant role in Anglo-Saxon myth and symbolism, representing power, strength, and prestige. The horse was seen as a symbol of high social status, and owning a horse was a sign of wealth and power. The horseman, on the other hand, represented a warrior and a leader, who rode into battle on horseback.

In the context of Hengist and Horsa, the horse and horseman motifs serve to enhance their status as powerful and prestigious figures. In addition to the practical and symbolic significance of the horse and horseman motifs, they also frequently played a role in Anglo-Saxon storytelling and epic poetry. The horse was often featured in stories and poems as a symbol of power, speed, and beauty, and the horseman was celebrated as a brave and noble warrior. An example can be seen in the Old English poem known only as The Wanderer where we read in stanza 92:

Hwær cwom mearg? Hwær cwom mago?

Hwær cwom maþþumgyfa?

Hwær cwom symbla gesetu?

Hwær sindon seledreamas?

Eala beorht bune!

Eala byrnwiga!

Eala þeodnes þrym!

Hu seo þrag gewat,

genap under nihthelm,

swa heo no wære.

Stondeð nu on lasteWhere is the horse gone? Where the rider?

Where the giver of treasure?

Where are the seats at the feast?

Where are the revels in the hall?Alas for the bright cup!

Alas for the mailed warrior!

Alas for the splendor of the prince!

How that time has passed away,

dark under the cover of night,

as if it had never been!

Here the connection of the horse-owning class with splendor, nobility and largesse, can be plainly seen. The horseman is a potent symbol in Anglo-Saxon folk-lore, and who would embody this symbol more completely, than a pair of semi divine brothers named “Stallion” and “Horse?” It is of some note that J. R. R. Tolkien, himself a notable Anglo-Saxonist and linguist in addition to being a renowned author of fiction, used a version of the stanza above in his novel, The Two Towers. Having researched English mythology extensively during his career, he posited that Hengist at least had a basis in historical fact, given that a figure named Hengest, who may be identifiable with the legendary brother of Horsa, appears in the Finnesburg Fragment and Beowulf.

In Lower Saxony and the Schleswig-Holstein regions in what is now Northern Germany, horse head gables, or gable signs adorned with two horsehead figures, were referred to as “Hengist and Hors” until around 1875 (Simek, 1993). This is regarded by some including Simek, as a survival of a Heathen tradition involving divine siblings, with possibly horse-like characteristics.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, a 12th-century British historian and chronicler, provides a colorful and imaginative account of Hengist and Horsa’s adventures in Britain. According to Geoffrey, the two were not merely warrior-leaders, but were actually half-brothers who descended from the legendary Trojan prince Brutus. This elevated their status from mere conquerors to heroic figures who helped to establish a new Trojan dynasty in Britain. This of course is far-fetched, and represents a trend in the scholarship of the time, toward tying famous heroes of all stripes to the mythic tradition of Troy, regardless of any apparent implausibility.

Hengist and Horsa are often associated with the Jutes, a Germanic people who lived in what is now Denmark and Germany. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals that recorded events in early England, the Jutes, along with the Saxons and the Angles, were among the groups of Germanic peoples who invaded and settled in Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by the monk Bede, provides further evidence of the Jutish origin of Hengist and Horsa. In his account, Bede describes the Jutes as one of the tribes that settled in Britain, and refers to Hengist and Horsa as leaders of the Jutish settlers. Bede, writing in the early 8th century, gives a slightly more nuanced account of the events surrounding Hengist and Horsa than did the admittedly biased Geoffery of Monmouth. According to Bede, the two warriors were not conquerors in the traditional sense, but rather leaders of a group of Germanic settlers who sought refuge in Britain from the Huns. Regardless of their motivations, however, the impact of their arrival was profound, as they helped to lay the foundation for the eventual dominance of the Anglo-Saxons in England.

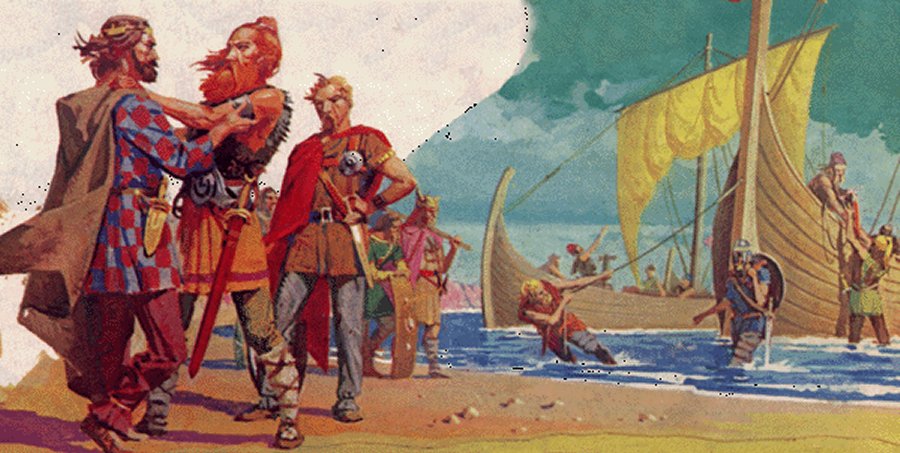

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle provides a brief overview of Hengist and Horsa’s arrival in Britain. According to the Chronicle, they were invited by the British king Vortigern to help defend against Pictish raiders from the north. However, once they had established a foothold in the country, the story holds that they quickly turned against their hosts and began a campaign of conquest that would lay the foundations for the later Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Who actually betrayed whom, is a matter of some debate and accounts naturally differ between pro British and pro Anglo-Saxon re-counters of the tale.

Regardless of the historical accuracy of these accounts, the legends surrounding Hengist and Horsa have had a lasting impact on English culture and tradition. For centuries, they have been celebrated as legendary warriors who helped to forge the English nation, and their exploits have been the subject of countless works of art, literature, and folklore.

In conclusion, Hengist and Horsa are figures of enduring fascination and importance in Anglo-Saxon mythology. While their historical significance is the subject of much debate, their legendary status as conquerors and heroes has helped to shape the identity and traditions of the English people. Whether as historical figures or as symbols of early England, Hengist and Horsa continue to captivate the imaginations of scholars, as well as Heathen reconstructionists.

Sources and References

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Anglo-Saxon-Chronicle

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ecclesiastical-History-of-the-English-People

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Geoffrey-of-Monmouth

- Hengist and Horsa. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hengist-and-Horsa

- Anglo-Saxon Mythology, Literature, and Society. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Anglo-Saxon-mythology-literature-and-society.

- Clemoes, P. (1997). The Anglo-Saxons. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Davidson, H. R. E. (1982). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books Ltd.

- James, E. (1991). The Franks. Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Kelly, S. E. (2003). Anglo-Saxon England: A New History. Tempus Publishing Ltd.

- Rollason, D. W. (2003). The Vikings in England: Settlement, Society, and Culture. Manchester University Press.

- Swanton, M. (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Phoenix Press.

- Grimm, J. and J. Grimm. (trans. J. S. Stallybrass) (1883). Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix. George Bell and Sons.

- Lindow, J. (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press.

- Simek, R. (1993). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D. S. Brewer.